Availability-Based Price Transparency

Transparency refers to the availability of prices or the disclosure of costs or margins. Understanding these differences is essential to develop an effective price transparency strategy.

(Note: This is a rather lengthy piece that explores three types of price transparency and describes a decision making framework for managers to design and implement a price transparency strategy for their organizations. To do justice to these concepts and ideas, I’ve divided the piece into three parts. This week’s post is Part 1 of 3. Parts 2 and 3 will follow consecutively in the next two weeks.

Price transparency is one of those concepts that evoke interest in everyone, managers and customers alike. At the first glance, the meaning of price transparency (dictionary definition: characterized by visibility or accessibility of information especially concerning business practices1) seems unambiguous, or shall we say, transparent. However, transparency in practice is a knotty and unwieldy idea in pricing strategy, for two main reasons.

The first reason is that price transparency can mean different things depending on who’s involved, and their objectives, perspectives, and mindsets. Having transparent pricing can imply that the company makes its prices readily available to potential customers while opaque pricing means that it screens them behind policies, contractual restrictions, or industry norms making it very difficult to find prices.

Alternatively, transparent pricing can mean that the company discloses some or all of its variable costs, or even all its costs, including ones that are fixed. A third possibility is that the company is keen on being completely candid about its business model and brave enough to reveal not only every cost component but also its markup factors, margins, unit sales, and revenue earned for the world (or certain selected constituents like customers, suppliers, etc.) to see, dissect, and learn from. The terrain of price transparency is vast and disjoint.

The second reason for potential confusion is that the different meanings of price transparency are often obscured. Most readers may agree with a general statement like, “Being transparent about prices with customers is a good thing.” But are they interpreting it in the same way? Or in the “correct” way as its author meant?

In my experience, managers, consultants, customers, not to mention academic researchers, routinely use price-related transparency terms interchangeably across different contexts and meanings without clearly defining them. This is problematic. The jumbled thinking about transparency makes it difficult to pinpoint what works and what doesn’t work, and to choose an effective price transparency strategy for the organization.

In this three-part post, I want to try and provide some clarity on price-related transparency by: (1) considering three different types, (2) naming and defining each type clearly so that each concept means one and one thing only, (3) exploring how each type of price-related transparency benefits and harms the company, and (4) providing a decision making framework for managers to design and implement a price transparency strategy for their brands and organizations.

The Three Meanings of Price-Related Transparency

To understand how researchers and pricing experts see transparency, let’s examine some of the definitions in the literature from experts who study price transparency. Note that this is by no means a comprehensive list, there are dozens of studies on price transparency, cost transparency, and other less-clearly specified forms of price-related transparency in the marketing literature alone, not to mention the vast economics, operations management, and other literatures.

My goal here is simply to illustrate the remarkably different ways in which transparency is conceived by different experts. In the list below, I have used the authors’ exact wording when it was available. When not clearly stated, I have edited the original words from the source text as lightly as possible. The source of each definition is cited in the footnotes.

Definitions of Price-Related Transparency in the Academic Literature

The degree to which market participants know the prevailing prices and characteristics or attributes of goods and services on offer2. (1)

The degree to which pricing information is sufficient and valid. Giving lots of options with prices attached increases sufficiency by allowing customers to form an understanding of available prices, making it easy to compare prices increases diagnosticity by supporting the customer’s decision making process3. (1)

Market transparency refers to the degree of customer awareness of product options and fair market prices for a given good4. (1)

Consumer price posting is whereby consumers post and share their purchase price information on the Internet5. (1)

Price transparency is the extent to which information about prices is available to buyers that organizes, explains, clarifies, or projects the contextual direction and/or rationale for the seller’s pricing6. (1) (2) (3)

The ability of buyers to see through seller’s costs and determine whether they are in line with the prices being charged7. (2)

The one-way sharing of cost information from a firm to its customers. It refers to the disclosure of the variable costs associated with a product’s production purchase to customers. In its strong form, the company divulges the variable costs associated with each component of producing a good. In a weaker form, the total variable costs to produce the good is disclosed8. (3)

Voluntary disclosure of cost information upfront by the salesperson at the front end of a negotiation9. (2)

The practice of revealing the unit costs of production to consumers10. (2)

Consumers know the firm’s marginal cost and can rationally infer the firm’s future price based on the firm’s current price and its actual marginal cost11. (2)

Estimates and breakdowns of costs provided by the firm or published by third-party infomediaries. (2)

Infographic highlighting the costs and processes involved in manufacturing various products. Revealing costs allows the company to showcase the otherwise hidden work that goes into making the product to customers. Customers are shown the markup charged by the company and compared favorably to markup charged by competitors12. (3)

The list shows there are three distinct types of price-related transparency definitions. They are about: (1) availability of pricing information, (2) disclosure of costs, and (3) disclosure of pricing performance variables. I have labeled each definition in the list with the numbers (1), (2), or (3) corresponding to these three definitions:

Definition 1: The Availability of Pricing Information

The degree to which prices are readily available to current and potential customers, and others such as suppliers, channel partners, and competitors in the marketplace.

Definition 2: The Disclosure of Costs

The degree to which some or all costs are disclosed to current and potential customers, and others such as suppliers, channel partners, and competitors in the marketplace.

Definition 3: The Disclosure of Pricing Performance Variables

The degree to which some or all costs and pricing performance variables (e.g., markup factors, margins, unit sales, and revenue) are disclosed to current and potential customers, and others such as suppliers, channel partners, and competitors in the marketplace.

Each type of price-related transparency is a matter of degree, rather than a binary variable indicating presence or absence.

The Availability of Pricing Information

In our role as consumers, we may take the ready availability of prices for granted. After all, many online retailers, supermarkets, automobile brands, hotels, and airlines (e.g., Southwest Airlines’ “transfarency” pricing) readily show prices on their own websites and apps, and through their marketing channels. These are examples of “high” price availability (see figure below) meaning that prices are readily available to customers at every point in their decision journey, even when they are just exploring and have no purchase intent. It also means that prices can be readily seen by competitors, investors, regulators, and everyone else.

A high price availability is not the norm. In many B2B industries like oilfield services and specialty chemicals, prices are not displayed in brochures, catalogs, or websites. Let’s say I am interested in Halliburton’s one of directional drilling systems that provide real-time drilling guidance. I can find detailed features and technical specifications of its products like the DrillDOC drilling collar or the SwellSim software. What is glaringly missing from these information-rich documents is price. To get even a ballpark estimate of what these things cost, I would have to contact a company sales rep and have a lengthy conversation. That is the only way to know the price.

Different settings vary in how much they vet prospects before revealing prices. In high-end real estate and medical devices, for example, prices aren’t revealed until the prospect provides evidence of their interest and ability to purchase. In some healthcare sectors like hospitals, customers may never learn prices until they receive the bill after treatment upon discharge. This is also true of auctions. Because of their participatory and dynamic nature, establishing the final price is coincident with purchase. The prior availability of pricing information has little meaning in the heat of competitive bidding.

Thinking about price availability also requires a consideration of how quickly price changes become widely available after they happen. In the online retailing space, for example, many retailers monitor competitors’ prices in real-time and adjust their prices so as to maintain consistent price differentiation. As Sanjeev Sularia observes, “Once you do have a solid grasp of your rivals, the challenge of intelligently beating their prices begins.” The same is true of airfares. Real-time monitoring requires real-time price availability. The variability in price availability shown in the figure above begs the question:

What degree of price availability is appropriate for your organization?

How available to make prices to customers (and others) is a key pricing strategy choice. Let’s consider the different reasons why companies choose to restrict price availability to help answer this question.

Withholding prices gives the seller pricing power.

In many B2B and healthcare spaces, managers view withholding prices as an essential competitive advantage and a powerful way to maintain pricing power. If your competitors don’t know your prices, the thinking goes, they won’t be able to undercut you. If one customer doesn’t know what another one is paying for your offerings, it strengthens your hand during price negotiations, allowing you to customize prices on the fly for each of your customers in almost unlimited ways. Opaque prices are flexible prices and empower the pricing organization. Obviously, this type of thinking views the customer as an adversary, as someone to be controlled or even hoodwinked.

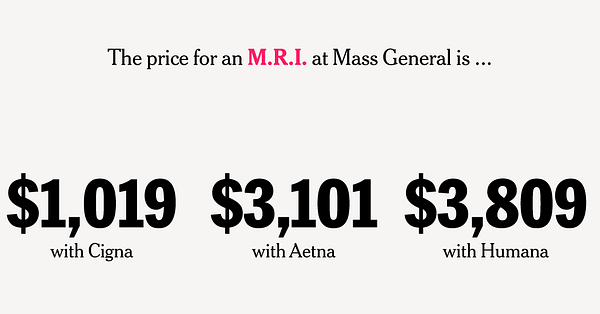

A case in point, US hospitals. According to a New York Times article that was published earlier this week:

“Until now, consumers had no way to know before they got the bill what prices they and their insurers would be paying. Some insurance companies have refused to provide the information when asked by patients and the employers that hired the companies to provide coverage. This secrecy has allowed hospitals to tell patients that they are getting “steep” discounts, while still charging them many times what a public program like Medicare is willing to pay. And it has left insurers with little incentive to negotiate well.”

Low price availability sows customer confusion and hides the seller’s pricing inconsistencies and illogic.

Even now, although required by federal law, many hospitals do not make their prices available for scrutiny. Why? Here’s the answer, again from the New York Times article,

“[Pricing information] shows hospitals are charging patients wildly different amounts for the same basic services: procedures as simple as an X-ray or a pregnancy test… Even for simple procedures, the difference can be thousands of dollars, enough to erase any potential savings…. And it provides numerous examples of major health insurers — some of the world’s largest companies, with billions in annual profits — negotiating surprisingly unfavorable rates for their customers. In many cases, insured patients are getting prices that are higher than they would if they pretended to have no coverage at all.”

The low price availability is a way to sow customer confusion and to hide the inconsistency and illogic behind the hospital’s pricing structure. Remarkably, this is an industry-wide phenomenon that even new regulation hasn’t yet been able to diminish. It can be argued that this non-transparent pricing approach is unethical and contravenes every principle endorsed by the Value Pricing Framework.

The shrouding of prices can extend to the conditions attached to customers’ sharing prices with other customers. In the medical devices industry, for example, some sellers write sales and service contracts that expressly forbid a customer from disclosing the final negotiated price not only to other customers but also to other interested entities such as insurance companies or patients13. Clearly, the seller’s intention is to withhold pricing information in order to maintain pricing power. Hospitals and healthcare insurers do the same thing for the same reason.

Consumers say they hate hidden prices but behave as if they love them.

The concern with making prices readily available is also found in many other industries. For example, online booking sites divide the prices of event tickets by itemizing mandatory charges and fees and not providing them until close to purchase. This procedure called price partitioning provides another temptation to sellers: it’s often not in customers’ best interests but it is too profitable to give up. To see why, consider this example from Michael Luca and Fiona Scott Morton:

“In 2015, StubHub set out to brand itself as a transparent ticket seller. Marketing materials promised: “No surprise fees at checkout.” When searching for tickets, users would see the prices, including all fees, up front to make it easier to search for tickets and know exactly what they’ll pay. However, the transparent approach turned out to be short lived.

StubHub ran an experiment in which they compared their transparent system to a system in which they showed the base ticket price on the main search page, and the full price only at checkout. StubHub users who weren’t shown fees until checkout spent about 21% more on tickets and were 14% more likely to complete a purchase compared with those who saw the total cost of a ticket upfront. The company dropped its transparent approach and went back to shrouded fees.”

Real estate sellers, art galleries, and restaurants among others, routinely practice low price availability in a slightly different way and for different reasons. They will post “Inquire for prices,” “Call for prices” or “Prices available upon request” notices and withhold prices from easy access.

When a prospect calls, they undergo a screening process of varying degrees and rigor before they are given price information. In these cases, some of the reasons are the same, gaining pricing power, throttling customer power, etc. But there are at least three other distinct reasons for reducing pricing availability.

Making the customer call for price raises their commitment to complete the buying journey.

For abstract products like art, customers are asked to inquire or call the seller for prices. In the example below, the art gallery is selling limited edition prints of the work of a renowned photographer. It readily provides details about the prints such as their size, material, and edition size on its website, but asks an interested buyer to call the gallery for information about prices and availability. This shrouding is not about pricing power. It has a purely psychological motive, to increase the customer’s commitment to the item by making them act. A small action, the inquiry, increases the chances of a larger action, the print’s purchase.

The “price available upon request” notice creates an aura of exclusivity and status.

In retail real estate listings, the norm is easy price availability. One exception is high-priced luxury listings. In the example below, the interested buyer is informed that the price is only available upon request. In addition to vetting serious buyers, the notice serves a branding purpose. It signals that the property is high-priced and unique. When it is combined with the exclusivity, uniqueness, and prestige of the listing, the lack of price transparency may also be indicative of the value uncertainty in the seller’s mind. As real-estate developer Aaron Katz put it:

“Given its absolute rarity, we didn’t want to presume what a buyer would be willing to pay. We decided a better approach would be to reach out to a select group of agents and individuals around the world who would be interested…and allow them to come to us with what they feel it’s worth.”

Withholding prices selectively pushes the customer towards certain product offerings and away from others.

Consider the restaurant below that offers daily specials to its customers by email every day. Its daily special for two comes with a bottle of wine and costs $48. The same special is available without wine, but that price is selectively withheld. The customer is asked to call the restaurant for the price. Why?

The previously mentioned reasons don’t apply in this case. Withholding price is not indicative of status or prestige nor does it necessarily increase customer commitment to purchase; after all, only one price on the menu is withheld, the others are readily available. The reason is by providing complete information for one alternative - the daily special with wine, the restaurant is encouraging the customer to buy that option instead of taking the additional effortful steps of calling the restaurant to find out the “without wine” daily special price, then evaluate this price, and finally decide whether to buy the with-wine or without-wine options. (Of course, this doesn’t apply to customers who don’t drink wine, they have no choice but to call).

Summary and Key Takeaways

Price transparency is a knotty concept with three distinct definitions. Managers need to be clear about which type of price transparency they are concerned with. In part 1, we explored the availability of prices. High price availability means that prices are available throughout the customer’s decision journey, whereas low availability means they are provided by the seller as late in the customer’s decision journey and as close to purchase as possible, and sometimes not until the purchase is made.

Prices can be withheld for various reasons that include gaining pricing power over buyers, sowing customer confusion, controlling the presentation of price components in a certain order, raising the customer’s commitment to complete the buying journey, creating an aura of exclusivity and status, and pushing people towards certain choices and away from others. The availability of prices is a powerful branding and customer influence tool when used judiciously.

In the next part, we will consider the other two types of price-related transparency, disclosure of costs, and disclosure of pricing performance variables.

This is the Merriam-Webster definition that seems most relevant to pricing. Transparency has other meanings also such as “having the property of transmitting light without appreciable scattering so that bodies lying beyond are seen clearly,” “fine or sheer enough to be seen through,” “free from pretense or deceit,” “easily detected or seen through,” and “readily understood.” In the context of pricing, these meanings coalesce to produce a positive aura around the concept of transparent pricing. Transparent pricing is perceived as customer-focused and authentic.

Soh, Christina, M. Lynne Markus, and Kim Huat Goh (2006), “Electronic marketplaces and price transparency: strategy, information technology, and success,” MIS Quarterly, 30(3), 705-723.

Miao, Li, and Anna S. Mattila (2007), “How and how much to reveal? The effects of price transparency on consumers' price perceptions,” Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 31(4), 530-545.

OShaughnessy, Eric J., and Robert M. Margolis (2017), The Value of Transparency in Distributed Solar PV Markets. National Renewable Energy Laboratory Technical Report No. NREL/TP-6A20-70095.

Zhang, Xubing, and Bo Jiang (2014), “Increasing price transparency: Implications of consumer price posting for consumers' haggling behavior and a seller's pricing strategies,” Journal of Interactive Marketing, 28(1), 68-85.

Hanna, Richard C., Katherine N. Lemon, and Gerald E. Smith (2019), “Is transparency a good thing? How online price transparency and variability can benefit firms and influence consumer decision making,” Business Horizons 62(2), 227-236.

Sinha, Indrajit (2000). Cost transparency: The net's real threat to prices and brands. Harvard Business Review, 78(2).

Mohan, B., Buell, R. W., & John, L. K. (2020). Lifting the veil: The benefits of cost transparency. Marketing Science, 39(6), 1105-1121.

Atefi, Y., Ahearne, M., Hohenberg, S., Hall, Z., & Zettelmeyer, F. (2020). Open negotiation: The back-end benefits of salespeople’s transparency in the front end. Journal of Marketing Research, 57(6), 1076-1094.

Truong, Ngoc Anh, and Georg Masopust (2021), "Cost transparency: A sales tool or a solid brand component?,” Special Issue Innovative Brand Management, 39-61.

Jiang, Baojun, K. Sudhir, and Tianxin Zou (2021) "Effects of Cost‐Information Transparency on Intertemporal Price Discrimination,” Production and Operations Management 30(2), 390-401.

Buell, Ryan (2019). Operational Transparency, Harvard Business Review, March-April 2019.

Pauly, Mark V., and Lawton R. Burns (2008), “Price transparency for medical devices,” Health Affairs 27(6), 1544-1553.