Disclosure-Based Price Transparency

Disclosing costs and margins seems admirably principled if risky, but is it more than virtue signaling or misguided activism that simply fizzles out?

This is Part 2 of a three-part post exploring price-related transparency and its implications for managers and researchers. The first part summarized the definitions of price-related transparency from the academic literature. These definitions are often used interchangeably across different contexts and meanings causing some confusion. Part 1 also explored availability-based price transparency and the reasons why companies withhold some or all prices from customers until as late in their decision journeys as possible. This post examines disclosure-based price transparency.

The Roots of Cost & Margin Disclosure Lie in the Philosophy of Radical Corporate Transparency

The disclosure of costs and margins by companies have their roots in the philosophy (or we could say, ideology) of radical corporate transparency. The idea has been percolating in business circles for the last several years, boosted by a number of influential business thinkers. The tenets of radical transparency are still evolving. Its implementation is choppy and at the moment, it is hard (at least for me) to separate the wheat from the chaff, i.e., companies paying lip service to an ill-formed and incomplete concept from those trying to sincerely practice these ideas in earnest.

Nevertheless, the fundamental principle behind radical transparency is alluring: honest and complete openness in business operations, internally with employees and externally with everyone in the wider world. The openness manifests in different ways depending on the organizational context and the thinker’s perspective. Here’s Ray Dalio’s take on radical transparency:

“I think the greatest tragedy of mankind is that people have ideas and opinions in their heads but don't have a process for properly examining these ideas to find out what's true. That creates a world of distortions. That's relevant to what we do, and I think it's relevant to all decision making. So when I say I believe in radical truth and radical transparency, all I mean is we take things that ordinarily people would hide, and we put them on the table, particularly mistakes, problems, and weaknesses. We put those on the table, and we look at them together. We don't hide them.”

And more directly relevant to price transparency, here’s Daniel Goleman’s view on the significance of radical transparency for different constituents of a business:

“The more transparent a market, economic theory holds, the healthier it will be. Information asymmetry — where sellers know crucial information that buyers cannot access — pollutes the market. Think toxic assets. The movement toward fuller transparency in the financial markets has a direct parallel in the ecological impacts of consumer goods. Signs suggest a trend toward greater marketplace openness about the environmental and health consequences of products — a trend with strong marketing implications.”

Once market participants – managers, workers, consumers, suppliers, policymakers – begin to consider the different impacts of products and services beyond immediate consumer buying behavior, seeking and producing open data to do so, the company’s costs are likely to be at the top of the list.

Few business variables are as informative as costs in decoding and diagnosing business impacts for external observers. For example, knowing the cost of labor in making a consumer product provides information about whether the workers who made the product are being paid a fair wage. (As the video shows, in the global apparel industry, the news is grim).

Along similar lines, the costs of ingredients can give insight into whether the company is compensating its suppliers fairly, a relevant issue in many global supply chains where there is a glaring asymmetry between the power of buyers (multinational corporations) and sellers (impoverished farmers, developing country entrepreneurs, etc.). And then, of course, there are the companies that take this disclosure a step further and make it part of their brand identity, value proposition, and in some cases, even their raison d'être. Let’s explore the motivations for why a company may disclose costs and other pricing performance variables.

Disclosure-Based Price Transparency

Despite the self-righteousness of many company founders and executives that often accompanies the disclosure of costs and the promise of worker, supplier, and consumer welfare resulting from it (see the Jim Cramer video below), in practice, disclosure-based price transparency is an elusive, fringe, and relatively rare pricing strategy.

The concept raises far more questions than we have answers for at the moment. We might even say that it is not a pricing strategy at all. Instead, it is a managerial ideology that has profound, and not always positive, consequences on the company’s pricing strategy. And strictly from a narrow business performance standpoint, there are many strong reasons not to disclose costs or margins. Among them:

Few pieces of proprietary information are as valuable as costs. For most companies, costs are the building blocks of a brand’s competitive advantage, and if not, at the least they are the yardsticks of incremental, day-to-day operating competence. Why on earth would a company want to reveal this valuable normally confidential information to potentially adversarial parties like its competitors and customers? (Yes, customers can turn adversarial in the blink of an eye). Note that the disclosure of margins is a bit trickier, it depends on which margins are being disclosed and for what reasons; business-level margins are commonly reported in public domains, while product-level margins are rarer to find but provide far more insight.

Revealing costs, even partially, gives powerful insights into a company’s business model. It shines a light on such things as which features and services it is marking up, which ones it is subsidizing, the sources of its revenue, the logic and calculation behind its pricing strategy, and so on.

Disclosing costs comes with legal exposure. For instance, when a company’s costs are transparent, a smaller customer may claim they are being over-charged when compared to a larger customer even when the costs to serve them are the same.

Even if its purpose is different and only tangentially related to pricing strategy, cost disclosure is a type of price-related transparency and has inevitable consequences on the company’s pricing strategy. Not all of these effects are welcome. When costs are disclosed, it puts a restraint on price levels that can be charged and the types of price structures that the company can employ. Customers notice price increases right away and the raises require stronger and cost-based justifications to succeed. Value-based pricing becomes virtually impossible to pull off. Price promotions become subject to vetting by customers and observers seeking evidence of unfairness or exploitative behavior. And the list of restrictions goes on. My point is that cost disclosure adds constraints and takes away flexibility from the company’s pricing strategy.

Despite these obvious disadvantages, many companies have been adopting cost and margin disclosure, and the trend only seems to be increasing. Let’s consider three distinct reasons for disclosing costs (and sometimes other pricing performance variables) to customers and others.

The Disclosure of Labor Costs (for Worker Welfare)

There are a number of movements, typically initiated by smaller, niche, socially conscious brands to increase the transparency of labor costs that go into their products and services. The impetus is findings like this one from the 2019 Tailored Wages report that covered 20 brands like Hugo Boss, Gucci, Nike, and H&M, and reported that:

“No major clothing brand is able to show that workers making their clothing in Asia, Africa, Central America or Eastern Europe are paid enough to escape the poverty trap…Whilst 85% of brands had some commitment to ensuring wages were enough to support workers’ basic needs, no brand was putting this into practice for any worker in countries where the vast majority of clothing is produced.”

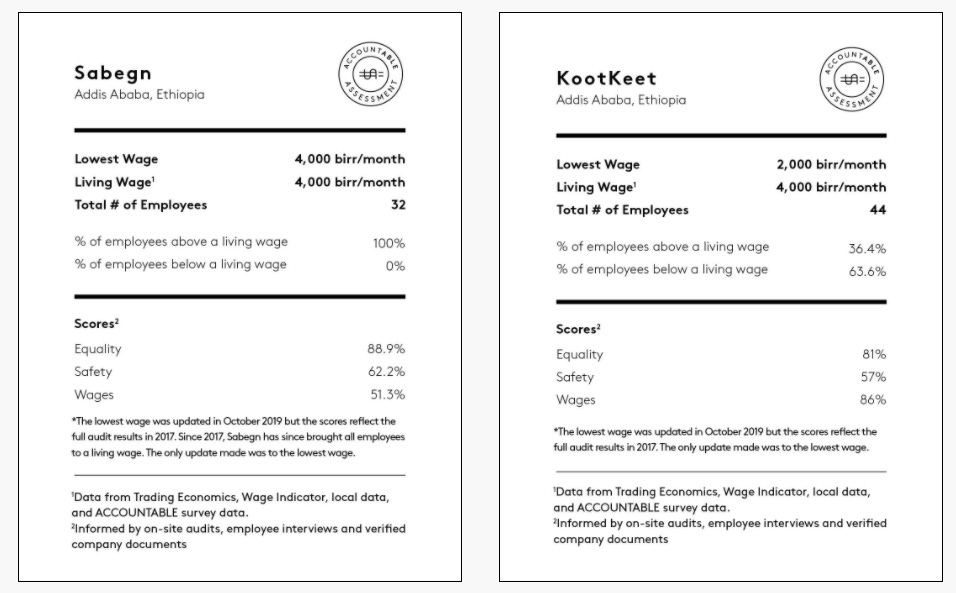

One labor cost transparency movement is the #LowestWageChallenge instituted by Able, a fashion brand that makes and sells jewelry and apparel. As the hash-tag says, this is a special form of transparency where the seller publishes the lowest wages it pays its workers. The brand has developed a reporting system that provides the information in a pithy format resembling a nutrition facts label (see below).

What does this cost disclosure accomplish? In the brand’s words:

“If we are to move the fashion industry to paying fair wages to its workers, we must first acknowledge where we are, and how far we have to go. In an industry where only 2% of manufacturing labor earns a living wage, and an estimated 75% are women, ABLE believes that publishing the lowest wages at our manufacturers protects the most vulnerable workers, and gives consumers clear data to make an informed choice. If they know what the bottom earns, everyone else from there is protected - not an average wage, or a labor cost per garment, but the lowest wage. For 100% of workers to earn a living wage it may take time, but nothing changes corporate exploitation like consumer demand (that’s you)….We think customers are ready for brands to be honest about the challenges facing fashion, and deserve to know whether or not the people who made the clothes on our body have been paid enough to meet their basic needs and live a life of dignity.”

The company also audited three of its suppliers in Ethiopia, reporting similar metrics for each one.

Able’s competitor, fashion brand Nisolo, also based in Nashville, also endorses the lowest wage challenge. Not only does it report the lowest wages paid by it and its suppliers, but it also explains in detail how its fellow brands within the apparel and fashion industry dodge responsibility for paying living wages, for instance, by saying that they pay “the legal minimum wage” even when they are far below living wages in many parts of the world.

Interestingly, neither Able nor Nisolo incorporates this lowest wage cost transparency into any of their other pricing strategies. Their promotions are similar to what we might see at any other low-transparency fashion retailer, from “extra 20% off already reduced items” promotions at Able to the “Give $50, Get $50” referral promotion at Nisolo. It’s almost as if the #LowestWageChallenge has been concocted by these company’s founders, but is divorced from having any meaningful impact on the purchase behavior of their customers.

Able’s founder and CEO Barret Ward told Fast Company,

“When people come to our website and see that information, they’ll be able to click through to see a very deep audit that’s been done on our manufacturing that shows all the good and all the bad. Our effort here is not to make a presentation that we’re perfect, but quite the opposite–it’s to be perfectly transparent.”

But the key question is how many customers really bother to see this information, care about it, and to what extent it affects their purchase decision or concern about worker welfare in the apparel industry.

The Disclosure of Purchase Costs (for Supplier Welfare)

Another variation on this theme of righteous cost disclosure is purchase cost transparency adopted in the coffee industry, again by niche, upscale coffee brands. One group of coffee companies has formed a collective to measure and report purchase cost transparency on their websites. A total of sixty-four coffee companies (and counting) have adopted the so-called Transparency Pledge.

The transparency pledge commits the coffee company to generate and publicly share purchasing reports including all its suppliers, the specific types and volume of coffee purchased from each one, and the FOB price paid on a per-pound basis. The signatories provide this information on their websites and in printed catalogs.

In its 2020 authenticity report, for example, one of the signees, Seattle Coffee Works reported that it purchased a total of 63,006 pounds of coffee and paid an average of $3.89 per pound. The company also reported that it paid its employees a starting wage of $17 per hour and full-time employees $24.50 per hour. Pachamama coffee, a Sacramento-based chain and a signee of the transparency pledge went even further, towards full price transparency. In addition to the names of suppliers and prices paid for coffee beans to them, Pachamama also disclosed how much revenue it earned, the price per cup it charged, plus its net profit and profit margin.

Like Able and Sisolo, for Seattle Coffee Works, Pachamama, and most other peer coffee companies who have signed the transparency pledge, providing detailed purchase cost information is only tangentially related to their customer focus. The primary interest of these coffee companies lies in reporting the purchase cost information from farmers in places like Ethiopia, Kenya, Peru, Honduras, and Guatemala. Whether customers read and process this information, and how they react is a secondary consideration. Tim Wendelboe, the owner of a Norwegian espresso bar describes this focus on coffee farmers, with no mention of his customers:

“I really hope that The Pledge can inspire more roasters to not only be transparent about their green coffee prices but also that farmers can use the information provided in the various transparency reports to have better leverage when negotiating the price of their coffee. Hopefully The Pledge will set a new standard when it comes to transparency and also a new benchmark for what the market price for quality coffee really is.”

Like the fashion labels that practice labor cost disclosure, the pricing strategies of the coffee companies do not appear to be transparent in any other way. By and large, these companies do not spend much effort in communicating purchase costs in any meaningful way to customers, or in considering whether customers are using this information or it’s having any effect on their perceptions.

The Disclosure of Variable Costs and Markup (for Building a Brand).

Can radical pricing transparency embodied by the disclosure of costs and margins be a viable branding strategy? Can it provide the foundation to build a successful brand? To answer these questions, we will turn to its most famous exponent (so far), the upscale fashion brand, Everlane. It’s interesting that here too, it’s a niche, relatively new, upscale apparel brand that decided to adopt radical transparency as its core value proposition.

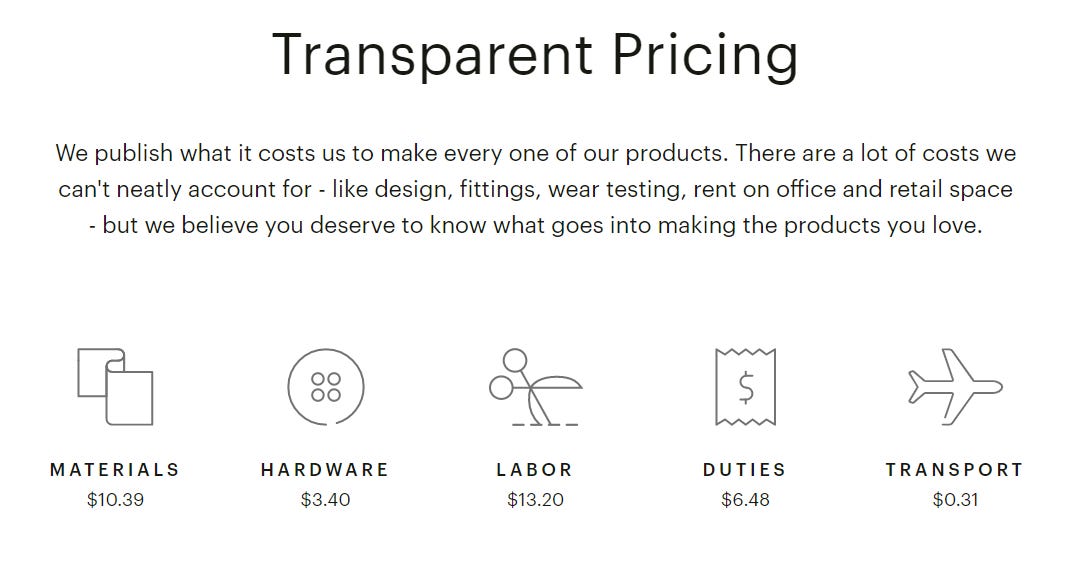

Everlane goes a step further than Able, Sisolo, or any of the aforementioned coffee companies in one way, and it doesn’t go far enough in others. Unlike the relatively narrow and focused concerns about the welfare of workers, or the welfare of low-power suppliers in the earlier cases, Everlane purports to be concerned with the welfare of all involved, its suppliers, workers, and customers. For every item it sells, the company discloses its variable costs: materials, hardware, labor, duties, and transportation. In the example below, for its chunky cardigan for Fall 2021 priced at $110, it reported costs of $33.78, a markup on variable costs of approximately 225%, which the customer has to compute themselves.

For many core products, Everlane additionally tallies the total variable costs and reports what its competitors charge for an equivalent item. The idea is to give customers as much information as is reasonable about the company’s inputs into its prices. Here’s a 2016 interview of Everlane’s CEO with Jim Kramer where he explains the logic behind Everlane’s value proposition and branding strategy of radical transparency:

Combined with other core values like making high-quality apparel that will last for years and working with factories that pass a compliance audit to evaluate factors like fair wages, reasonable hours, and environmental impact, this radically transparent pricing forms a compelling and complete value proposition that many customers find attractive.

Another distinctive aspect of Everlane is that its adoption of radical transparency carries over to some of its price promotions. In its annual “Choose What You Pay” Winter event in late December, Everlane sells a considerable proportion of its merchandise using a transparent, customer-empowered promotion. It works as shown in the example below. For the black pants shown, the customer can choose one of three prices for the regularly $98 priced item. Each price comes with an explanation of how much of Everlane’s costs it covers, giving customers the choice to support Everlane’s operations at different levels.

This all sounds great. The problem is that evidence suggests that Everlane hasn’t delivered on its promise of harvesting the benefits of radical transparency. The New York Times ran a story last July reporting systemic mistreatment of employees and unethical behavior by the company’s senior executives. Among other things, former employees reported union-busting, a culture of favoritism, a lack of consistent policies around promotions (the personnel kind, not the pricing kind), and behaviors such as using inappropriate language to talk about Black models, violating subordinates’ personal space, and punishing employees for speaking up. Obviously, this is the diametric opposite of the spirit underlying radical transparency.

The Everlane case contrasts the cases of Able, Sisolo, Pachanama and others. Where the other companies were hard-pressed to convert their good intentions into practical customer-directed pricing actions grounded in transparency, Everlane’s promise of radical transparency is entirely customer-focused with little regard for the well-being of its own employees. It’s not surprising that even with meaningful cost disclosures and clever transparency-based price promotions, the promise rings hollow and fails to deliver.

Conclusion

Where does this leave us? I began this discussion with an unalloyed optimistic outlook as I explored disclosure-based price transparency. The idea of disclosing costs and margins to customers as part of a deliberate overall pricing strategy is promising. It can empower customers, helping them to make more informed decisions.

Yet, the cases I described were those of company founders enamored with virtue signaling or social activism, without really caring much about whether their customers’ reactions to these disclosures or contrarily paying lip service to the concept and using it as an advertising slogan or a tactical price promotion in the case of Everlane. I have not yet been able to find a skillful and ethical exponent of disclosure-based price transparency.