Pricing Case Study: A Balanced Look at Dishoom’s Matka Promotion

At first glance, the promo appears to be a big win for the customer and an avoidable loss for the restaurant. It's a bit more complicated than that.

Dishoom is one of my favorite restaurants in London. Every time I’ve been to the UK over the past fifteen years or so, I have eaten at a Dishoom at least once. It’s an excellent overall dining experience with delicious, innovative food options, a nice ambiance, and attentive service (although sometimes you have to wait in a queue). Dishoom’s brand ethos is captivating. If you have never eaten at Dishoom and aren’t familiar with the restaurant chain, here is a nice introduction.

But this post isn’t about Dishoom’s Dharma or its food or its appealing idea of service around seva or its customer experience. It is about Dishoom’s pricing strategy, or more accurately, one specific aspect of it, its Matka promotion. Dishoom has been running this somewhat under-the-radar promotion since at least 2015, and likely since its inception. Limited to its regulars in the early years, it has since expanded to anyone who asks to participate.

Every so often, someone discovers this secret promotion1 and then writes gushingly about it. Most recently, there was an insightful article by Richard Shotton in Marketing Week, who was affected by his experience with the Matka promotion…

“So much so that it’s quite likely we’ll choose to eat at Dishoom again, just to get a roll of that dice. Because, next time, who knows? A delicious meal — and it could be free. We’re bound to spread the word.”

In this post, I want to assess the Matka promotion critically, considering it through the lens of pricing strategy. Is it one-sided, favoring customers only, as many writers have written? What are its implications for Dishoom?

What is Dishoom’s Matka promotion?

Dishoom’s Matka promotion is what academics might call a two-stage probabilistic price promotion. In Dishoom’s own words:

‘Sixer Dalo, Free Khao!’ – Loosely translated: Roll a six, your meal’s on us! Matka (मटका - pronounced: mut-ka) is a word with many meanings. It’s Hindi for a pot, and it also refers to the illegal underground lottery that sprang up in Bombay in 1962.

The two-stage nature of this promotion makes it different from a simple lottery- or sweepstakes-type promotion (like, for example, the Starbucks for Life promotion, or the currently running Minute Maid’s “Bring the Juice” giveaway, co-branded with WWE).

In the first stage of the Matka promotion that we might call the “activation” stage, Dishoom’s customer has to proactively ask a staff member for a token2, which comes attached to a keyring (see below for different versions of the token from different restaurant locations). By acquiring the token, they have activated the promotion for themselves.

Then the customer carries it around, and the next time they visit a Dishoom and finish their meal before 6 pm on a weekday, and ask the server at the time of paying their bill, they have the chance to roll the dice in a ceremonial fashion at the end of their meal. This is the promotion’s second stage, which we might call the “enactment” stage.

Performing the act of rolling the dice is enacting the promotion’s requirement. If they roll a six, the customer’s entire bill for that visit is comped (for up to 12 people); if not, they have to pay for it like everyone else. This is the probabilistic aspect of the promotion that Richard Shotton and others, who admire this promotion, have focused on. The video below, posted by a Dishoom customer, describes the experience of participating in the promotion:

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

On the face of it, this seems like a win-lose price promotion — a win for the customer and a loss for Dishoom. A typical loyal Dishoom customer loves going there, enjoys the food and experience tremendously, and feels they are already getting value for money. (After all, there are often long lines to get in.) To then get an entire meal comped seems like delicious icing on the cake. Plus, there’s the thrill of winning a free meal. Shotton talks about this in detail in his piece. See this customer’s visceral reaction to rolling a six and winning a free meal unexpectedly:

For Dishoom, on the other hand, this doesn’t sound like a good idea. Why give one in six customers who would have come to your restaurant anyway, eaten and spent money anyway, free food for their entire party? On first glance, it seems like a costly, unnecessary promotion to run, an expense that can easily be cut out without any ramifications. I find this to be the most interesting question about the Matka promotion, and I will try to answer it here. But first, let’s look at other similar promotions to truly appreciate the uniqueness of the Matka promotion.

Other (Somewhat) Similar Promotions

I don’t know of any other two-stage probabilistic promotions exactly like Dishoom’s Matka, but here are some examples of price promotions that share some of its characteristics.

Nando’s High Five Card. The South African restaurant chain Nando’s has given out a reward shrouded in secrecy, called the Black Card or High Five card, for over two decades. The card grants its holder and their friends free meals at Nando’s restaurants for one year (with the possibility of renewal), although it’s not clear what frequency or how many friends are covered, nor the terms of its renewal are known.

All the public-domain discussions suggest that the card has only been given to celebrities and influencers after they have promoted the Nando’s brand significantly. (No word if they also received other remuneration beyond free food at a Nando’s). The High Five card is not really a price promotion for normal customers in the sense that Dishoom’s Matka promotion is, and there’s nothing probabilistic about it. Rather, it is compensation given to influencers and spokespeople by using a buzzy scarcity marketing tactic. It’s worth noting here that other fast food chains like McDonald’s, with its gold card that gets its owner free McDonald’s food for life, and Chipotle with its celebrity card, have used similar approaches, emphasizing rarity and secretiveness.

Mattress Mack’s Free Furniture. Here in Houston, we have an iconic brand called Gallery Furniture, owned by Jim “Mattress Mack” McIngvale, who is greatly admired in the city for his philanthropy (but not so much for his politics). For the past several years, he has run high-value probabilistic promotions. For instance, in one promotion, if customers purchased furniture of a certain value from his store, and if the Houston Astros baseball team won the World Series (they’ve won twice, in 2017 and 2022), then the entire amount spent would be refunded to them. Here he is explaining one of his “Astros win-free furniture” promotions.

His stores are very popular in Houston, which begs the question: How can Mattress Mack afford to pay for this promotion that potentially gives thousands of Houstonians thousands of dollars apiece, as he had to do when the Astros won the World Series in 2022? In case you are wondering, here’s how:

Mattress Mack left Las Vegas with a wheelbarrow full of cash. Houston furniture store owner Jim “Mattress Mack” McIngvale was back in the valley Thursday night to collect $40 million of his record $72.6 million in winning wagers on the Houston Astros to win the World Series. He was presented with a check for $30 million at Caesars Palace for a $3 million bet he placed in May at 10-1 odds at Caesars Sportsbook. After having dinner at Caesars Palace, McIngvale headed to Aria to collect his $10 million in winnings from a $2 million wager he placed in July at 5-1 odds at the BetMGM sportsbook at Bellagio. After sleeping for three hours in his free room, McIngvale went to the casino cage at 3 a.m. Friday to collect his $10 million. In cash. He then headed to the airport, where he loaded the stacks of cash into a wheelbarrow and then onto his private plane for the trip back to Houston….

McIngvale’s bets were the latest in a series of wagers to reduce risk on furniture promotions. In this case, customers who bought $3,000 or more of furniture were guaranteed to either get their money back or double their money back (depending on when they took part in the promotion) if Houston won it all. He placed a total of $10 million in World Series futures bets on the Astros.

Random freebies from Crumbl, Starbucks, etc. Many restaurants and coffee chains are known to randomly offer free items to their customers. For instance, you might walk into a Crumbl Cookie or a Starbucks store and be offered a free cookie or a free frappuccino just because. Many companies make this sort of giving out random rewards a part of their employees’ job description, where they are empowered (and even encouraged) to give out free products to their customers.

In other cases, some line employees may do this on their own initiative. This is similar to the Matka promotion in the sense that there’s chance involved. What is different is that it is entirely random without any involvement or volitional action by the customer (i.e., no clear activation or enactment); the customer just gets lucky. However, such random rewards can be particularly effective in generating an emotional response in those bestowed with the reward and leaving a mark, as in the case of this Redditor:

I'm a regular at my local Starbucks, and i couldn't find my wallet. I was so embarrassed i was tearing up, apologizing like crazy, and i was more than willing to go park and look for it and just come inside to pay for it and get it...and the barista just gave it to me and said not to worry. I cannot express how surprised and grateful i was, and proceeded to cry on the way to work with my pink drink.

The Favorable Economics of the Matka Promotion from Dishoom’s Perspective

Although the Matka promotion appears to be a win for the customer and a loss for the restaurant, that really is not the case. In fact, it is an extremely creative, moderate-cost promotion that is precisely calibrated, with the potential to reap serious financial rewards for the restaurant.

A probabilistic free offer equates to a certain discount that is much, much lower. A one in six chance of getting your bill waived is the same thing as getting a 16.67% discount on your bill. For the restaurant, it equates to giving out a 16.67% discount to customers on weekdays before 6 pm. But that is if every single person walking into the restaurant has a token and remembers to use it on every single visit.

In reality, both the percentage of customers having tokens and the subset of possessors actually remembering to use them will be much smaller, and therefore, the effective discount will be significantly smaller. For instance, if both numbers are 50% (half the patrons on any weekday have a token, and half of them use it), the effective discount will be just over 4%. And even this is most likely an overestimate! Thus, the Matka promotion’s discount is moderate, yet it generates buzz because it appears to be generous and over-the-top. Although it sounds like a great deal on its face, the Matka promotion is much cheaper than virtually any social hour menu at a similar restaurant, where the discount could be 40%, 50%, or even greater, and given to everyone until the happy hour ends.

Cleverly designed and enforced constraints around the promotion make it business-friendly. Although it seems spontaneous and maganimous, in reality, getting a free meal through the Matka promotion requires the customer to jump through ten consecutive hoops spanning time, requiring memory, and even physical effort. The customer has to work hard every step of the way to get their Gunpowder Potatoes and House Black Daal for free. This is what the customer has to do:

Get your hands on the token during a visit to Dishoom,

Don’t lose the token,

Decide to eat at a Dishoom again,

Remember to bring the token with you on the next visit to a Dishoom location (don’t leave it at home!),

Visit on a weekday morning or afternoon,

Visit early enough so that your party has eaten and is ready to pay the check before the clock strikes 6 pm,

Remember to use the token at that time,

Be outgoing enough to tell the server you want to play the Matka game,

Be willing to participate in its performance by rolling the dice while diners around you stare, i.e., become the center of a spectacle, and

Roll a 6.

In effect, a lot of things have to happen in sequence for the customer to win the free meal, and most of these actions have to be effortfully performed by the customer over a period of time, making the actual number of customers who “win” the promotion and the actual discount earned by Dishoom’s customers both small values (likely a small fraction of all diners).

In fact, it can be argued that because of these two characteristics, the probabilistic aspect and the effortful participation by customers, Dishoom’s Matka promotion dominates any blanket discount or offer from any restaurant, whether it is happy hour pricing, a cheaper lunch menu, or things like BOGO offers. Its narrow applicability makes it high-value for the business, and its upfront costs (from getting these high-quality keyring tokens made) seem modest.

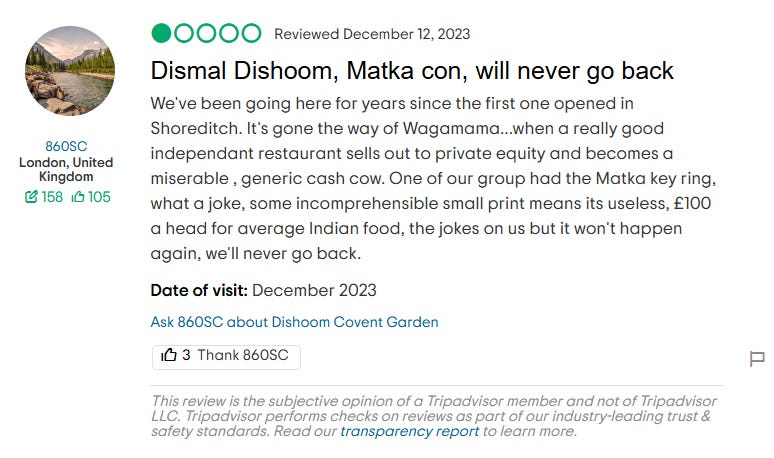

Does this mean everyone likes the Matka promotion? No. Despite all the positives, some Dishoom customers still haven’t been won over, as evidenced by this TripAdvisor review.

In pricing strategy, paraphrasing the famous adage, you can never make all your customers love your promotion all the time, no matter how amazing it is.

With all the social media posts and business pieces, the Matka promotion is not really that secret anymore. There are hundreds of TikTok videos about it, numerous references to it on Reddit, various review sites, and so on. I first heard about it several years ago in the context of a similar (but non-probabilistic) promotion by another UK-based restaurant chain called Nando, which offers a black card promotion with some similarities.

In its early days, each restaurant used to give out tokens to its regulars; nowadays, you can ask for the token and get it upon request.