Pricing Case Study: The Dark Side of Costco's Pricing Strategy

A combination of self-imposed low markup and an outsized reliance on membership dues leads to heavy-handedness and detracts from the experience of customers, employees, and suppliers.

Having been a Costco member and a regular shopper for many years, I can attest to the fact that the overall buying experience at Costco is pretty good, from the high quality of Kirkland Signature products to the flea market feel of discovering and trying seasonal and limited-time items on sale, to the low prices and exceptional value of the purchases. (Some aspects, like the teeming crowds, the long checkout lines, and the struggle for parking, are put-offs, but they are understandable and perhaps even validate the choice to shop at Costco).

As someone who’s interested in pricing strategy, I am also an “informed fan” of the synergy and customer orientation behind Costco’s pricing strategy. I’ve written previously about various aspects of Costco’s pricing strategy, such as its exemplary use of a two-part pricing approach to create a highly appealing, differentiated offering, the effectiveness of its hot dog and soda’s iconic $1.50 price point, and its inadvertent but effective use of a price vocabulary to generate customer loyalty.

However, when you consider the Costco shopping experience closely as a customer, some distinctly jarring pain points can emerge. On one shopping trip several years ago, for example, I forgot my Costco membership card and had to leave a full cart of groceries unattended and walk over to the membership desk to validate that I was a Costco member. That’s because the cashier refused to check me out without proof of membership. It took me an extra hour or so to complete my Costco trip that day.

Another time, we went shopping with family members at a Costco store in their town. When the time came to check out, my relative wanted to pay, but Costo refused to take their money (the only instance of a retailer doing this I’ve experienced). The cashier made us feel uncomfortable and tried to sell a membership to my family member. In the end, I ended up paying for the purchases after undergoing another membership validation exercise. Other members have had similar experiences.

Under the soft, gooey kumbaya fandom that surrounds the Costco brand like a halo, there are some hard, spiky edges in how Costco treats its customers members. Its suppliers and employees also don’t always fare as well as they could.

As I want to explore in this post, these negative experiences directly have to do with Costco’s pricing strategy, particularly the way it has chosen to execute its price structure. (Here’s more on price structures; for more on price execution, see my post on the Value Pricing Framework). The dark side of Costco’s pricing strategy provides useful core lessons about the complex relationship between price structures and customer experience.

Costco’s membership-markup pricing model

Costco is the poster child for the two-part pricing model that I call the “membership-markup” pricing model. It has one of the more straightforward and simple-to-explain price structures in retailing that is very effective.

Membership fee. Costco’s customers have to sign up and pay an annual membership fee on a subscription basis for the right to purchase products in its warehouses and online. The membership fee is currently $60 for a regular membership, also called the Gold Star membership, and $120 for an executive membership, which returns the user a 2% cash refund on purchases every year, further increasing their shopping commitment to Costco. Costco incurs some costs to administer the customer’s membership (e.g., making a card when the customer joins), but that’s about it. The membership fee is the high-margin component of Costco’s price structure.

Markup. Costco uses a dual-impact restricted markup pricing approach on product sales to offer significantly lower prices than the competition. The dual impact is from relatively smaller markups on relatively lower prices paid directly to manufacturers for buying in bulk. As famously reported, the first prong is the restrictive and relatively low markups that the company has held on to for decades:

Costco has to be lean because Brotman and Sinegal long ago established a rule that no branded item could be marked up more than 14% and no Kirkland Signature item more than 15% over cost. It is an inviolate line: the very value proposition of the company.

The second prong of the markup pricing is the low purchase prices from suppliers. This price structure is well-differentiated from its direct competitors, as discussed below, but it is no secret. As Costco explains at the very beginning of its 2022 Annual Report:

“Offering our members low prices on a limited selection of nationally-branded and private-label products in a wide range of categories will produce high sales volumes and rapid inventory turnover. When combined with the operating efficiencies achieved by volume purchasing, efficient distribution and reduced handling of merchandise in no-frills, self service warehouse facilities, these volumes and turnover enable us to operate profitably at significantly lower gross margins (net sales less merchandise costs) than most other retailers.”

Bryne Hobart summarizes the membership-markup model this way:

Costco, for example, chooses to make money from memberships instead of on a per-product basis—and doing so lowers the customer's marginal cost, conditional on their sending Costco enough business to amortize the fixed cost of opening giant warehouses and keeping them well-stocked. (This model has the added benefit of leading to high inventory turnover, and producing the kind of scale that lets the buyer negotiate aggressively with suppliers.)

The profit levers of Costco, Walmart and Target

We can compare Costco’s membership-markup pricing to the more standard markup method used by Walmart and Target to get a sense of the importance of membership fees to each retailer. Although I included Amazon in my initial set, Amazon has a more complex price structure, it loses money (a lot!) from product sales, it has negative gross margins, and it doesn’t reveal data about memberships (which deliver different values like Thursday Night Football games). Combined with its technology positioning and the weight of its AWS and digital advertising divisions, I concluded that Amazon is not comparable to Costco, Walmart, and Target for the present discussion.

Costco’s numbers: I calculated the two profitability drivers (membership fees and margin from sales) of Costco’s membership-markup pricing model from the information in its latest 10-Q report. For the three months ending May 7, 2023, Costco reported sales of $52.6 billion, revenue from membership fees of $1.04 billion, and operating expenses of $52 billion. Essentially, Costco earned a gross margin of 10.3%, meaning that 62% of its operating income was derived from membership fees, while the rest came from product sales. This is no anomaly. Over all of 2022, Costco’s gross margin was 10.5%, and membership fees contributed to 54% of its operating income.

Walmart’s numbers: This is in stark contrast to its most comparable competitor, Walmart. Walmart reported sales of $160.3 billion in the latest quarter that ended on July 31, 2023. Its cost of sales was $121.9 billion, resulting in a much healthier gross margin of 24%. Its membership revenue was about $1.3 billion (from Sam’s Club and Walmart+ memberships), contributing about 18.4% to operating income. Walmart is making far more money by marking up its merchandise higher and relying far less on membership revenues than Costco.

Target’s numbers. Unlike Walmart and Costco, Target doesn’t report membership revenue separately because it doesn’t offer memberships in any meaningful way. In its most recent quarter, which ended July 29, 203, Target reported sales of $24.4 billion and cost of sales of $17.8 billion. Its gross margin of 27% was the highest of the three retailers.

The table shows the differences between Costco and its main competitors. Costco is able to sustain a significantly low gross margin because it supplements revenue from memberships. The table also confirms that Walmart and Target practice a traditional (to retail) form of markup pricing with substantially higher markups. Costco practices a different membership-markup pricing strategy that relies heavily on memberships.Both pillars of Costco’s strategy, a self-imposed low gross margin and a heavier reliance on membership revenue to generate profit, have negative repercussions for Costco’s constituents, including customers, frontline employees, and suppliers. This is the dark side of Costco’s pricing strategy I want to explore further.

What price realization and plugging the price realization gap mean for Costco’s constituents

The ultimate success of any pricing strategy, no matter how harmonious and differentiated it is, lies in price execution. The company must minimize the gap between the asked-for price and the realized price. Membership and markup each bring distinct challenges to realizing price for Costco.

Because Costco depends so heavily on membership revenue for profit, its price realization has a lot to do with managing membership sales, ensuring that it keeps signing on more paying members any way it can. It must build a wall to keep non-members out while concurrently offering them a gate to let them in and become active dues-paying members. Instead of unit sales or sales revenue, Costco’s primary profitability metrics are the size of its membership base and its churn rate. Costco is more similar in its price execution objectives to Netflix than it is to Walmart.

This is where it gets interesting, and we get to the main point behind the dark side of Costco’s pricing strategy: For Costco, managing memberships to realize price necessarily requires making some hard and unpleasant customer experience decisions. It means policing, denying, requiring hoop-jumping, being rude, and cracking down ruthlessly and repeatedly, all for the purpose of keeping non-members out, encouraging non-members to sign on and getting current members to renew. None of these goals are possible without injecting a significant degree of unpleasantness into the shopping experience of members and the working experience of frontline employees.

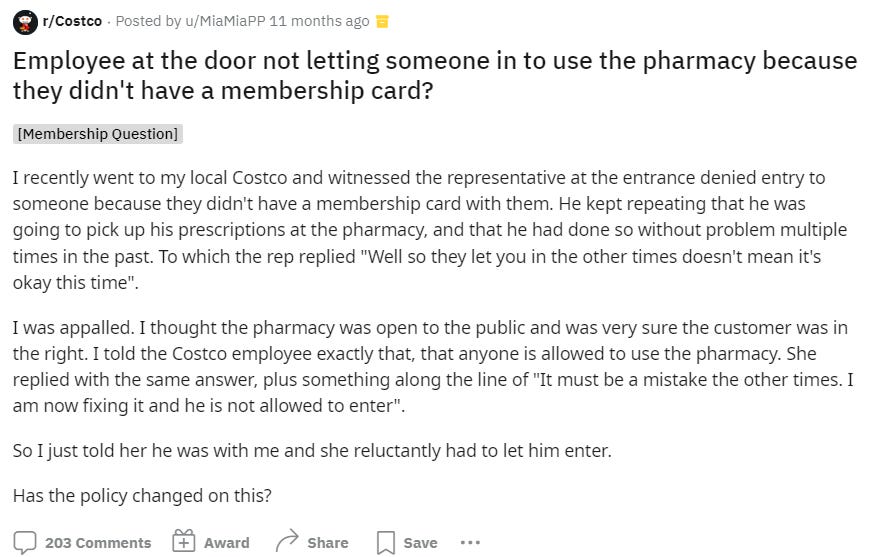

Here are three specific methods that Costco uses actively to manage its memberships and protect its profits that illustrate this point. To explore them vividly, I have provided posts from Costco’s customers and employees from the r/Costco subreddit. (Note: Each post is linked if you want to go down a rabbit hole and read the comments).

1. Cracking down on membership sharing

In its economic impact, membership sharing is as much of a problem for Costco as password sharing is for Netflix, or even more. When people share their membership with others, whether it is family members, neighbors, acquaintances, or just random strangers that they met in the store, it is a profit leak for Costco, pure and simple.

Costco tries to plug this leak throughout the shopper’s journey, but especially at the beginning and end, when the shopper enters the store and when they check out, in ways that are unavoidably unpleasant to customers and not always fair. In the stories below, customers report being disrespected, treated like shoplifters, accused, shouted at, humiliated, and harassed by employees. You can see just how awful the policing experience can be for everyone involved.

2. Policing self-checkout

Another profit leak that can occur is when non-members try to game the system and purchase Costco products in the store or through another channel. The most recent example is self-checkout. So it’s not surprising that Costco has now implemented strict procedures to check not only membership cards but also photo identification of the shopper to ensure that only members can use self-checkout. Costco’s spokesperson told a Wall Street Journal reporter in June:

“Since expanding our self-service checkout, we’ve noticed that nonmember shoppers have been using membership cards that do not belong to them. We don’t feel it’s right that nonmembers receive the same benefits and pricing as our members.”

Costco’s executives “don’t feel it’s right” because this shopping behavior is a significant profit leak for their membership-markup pricing model. The truth is that most members don’t care about this issue, and if anything, the policing activities by employees slow down the checkout lines and degrade the self-checkout experience of Costco’s members. It’s noteworthy that neither Costco’s shoppers nor its employees like the policing, as the following stories illustrate:

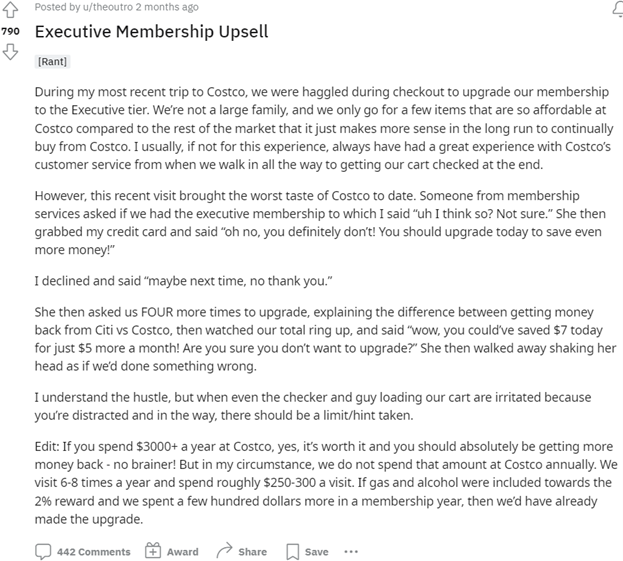

3. Upselling Executive memberships

A third approach to managing memberships that will appear familiar to pricing practitioners is upselling current customers from the cheaper Gold Star membership to the more expensive Executive membership. It’s classic trading up in a Good-better-best price structure.

Furthermore, the economics of Costco’s profitability discussed earlier means that a customer buying the Executive membership will be far more profitable to Costco than a regular member, regardless of how much they purchase over the course of the year. Each Executive member contributes $60 more to the bottom line at the outset and then approximately 8% gross margin for their purchases, which are presumably more than those of a regular member. But even if they are the same or less, Costco still comes out with a higher aggregate profit.

In services marketing, upselling activities by employees rarely provide a pleasant experience for customers. It is no different for Costco customers and employees, as the following stories illustrate. The first one describes a pushy Costco membership services employee, leading to “the worst taste of Costco to date.” The second post mocks the efforts of a gas station attendant trying to sell an Executive membership.

What “operating efficiencies achieved by volume purchasing” mean for Costco’s constituents

As we saw earlier, Costco attributed the operating efficiencies it achieved by purchasing in volume as a significant component of its business strategy that contributes to successful outcomes. This is the “markup” piece of its membership-markup pricing model.

While Costco deliberately chooses to accept a low gross margin as a pillar of its harmonious pricing strategy, its suppliers are forced to tag along and accept correspondingly lower margins if they want to do business with Costco. What’s more, the company is quite open about its heavy-handedness with suppliers. For instance, as reported in a Bloomberg article, in an analyst call after reporting quarterly earnings in 2018, Costco’s CFO Richard Galanti said:

“You’re seeing significant savings -- in some cases, a small amount from us -- but more from our suppliers because it drives more sales….The brands need to come down in price, too, because they’re losing market share.”

Given its size and scale, Costco has many degrees of freedom to accomplish supplier margin reduction. For instance, one approach it has used in the past is to have vendors take on a larger proportion of the costs when running limited-time promotions on their items at Costco. Another is to prod vendors to lower prices over time so that Costco, in turn, can offer lower prices to its customers.

Larger brands, such as CPG behemoths that sell a few SKUs of their vast product lines through Costco, have considerable flexibility in this respect. As I’ve discussed in other places, their incremental costs of manufacturing the products to sell in Costco are often low (e.g., by using spare capacity or other low marginal cost resources). Consequently, they can still make money at significantly lower prices.

However, as the following somewhat lengthy post explains, smaller vendors may not enjoy the same flexibility or success. Moreover, the asymmetric power in the retailer-manufacturer relationship means that they are at a disadvantage in negotiating terms and may have to accept lower, perhaps even unsustainable, margins to supply to Costco.

It is worth noting here that the sort of negative experience described here is not unique to Costco. Its direct competitors, Walmart, Target, and others, have been accused of a similar modus operandi by their respective suppliers.

Lessons from this case study

Costco is held up by many, including myself, as a practitioner of exemplary pricing strategy. However, every pricing strategy, no matter how harmonious, differentiated, or clever, must grapple with the problem of price execution and ultimately delivering a profit.

Everyone must compromise. There are tradeoffs for everyone involved when membership-markup pricing is used instead of traditional markup pricing. What customers gain in lower prices and exceptional value in their purchases, they lose in the negative experience during checkout and, to a lesser extent, in other parts of their shopping journey. What employees gain in higher pay and better benefits, they lose in having to administer the negative aspects of the membership policing actions. What suppliers gain in large-scale, reliable orders and predictable cash flows, they lose in having to settle for wafer-thin margins and a powerful partner that always has them on a tight leash. Whether these tradeoffs are worth it will depend on the individuals.

Price execution is essential. No matter what type of pricing strategy you practice, there are one or more components that deliver profit to the organization. Without decisions and actions to execute them, these components remain theoretical. Within the company, decision makers must establish the policies, line managers must enforce them, and frontline employees must enact them, all in the service of realizing price and delivering the profit. This typically involves taking actions or imposing restrictions on customers that generate profit or stop the profit from leaking.

In Costco’s case, the profit is derived through membership and markup, with a heavier reliance on the higher-margin membership revenue. Consequently, despite its good intentions, customer-oriented and employee-focused mindset, and best-in-class business strategy, the company has no choice but to adopt aversive policies to manage memberships that are bound to be unpleasant for those involved. There is no way around it.

Zero-sum games abound. All three instances of membership management and the retailer-supplier relationship dynamics that we saw are zero-sum games. Costco only wins (in the sense of earning a profit or preventing a profit leak) when the customer loses (by paying for the membership and using it in a restrictive way). Conversely, the customer only wins (for example, by buying products without a membership) when Costco loses (by profit leakage).

This is the main lesson that we can learn from this case study on the dark side of Costco’s pricing strategy. In the end, every pricing strategy, no matter how thoughtfully, ethically, and cleverly constructed, must culminate in a zero-sum game being played out between the company’s agents and its constituents, in this case, its customers, employees, and suppliers.

The truth is that in pricing, zero-sum games abound, and they are essential for the sustainability of pricing models.