Why Shrinkflation Works So Well (and When it Doesn’t)

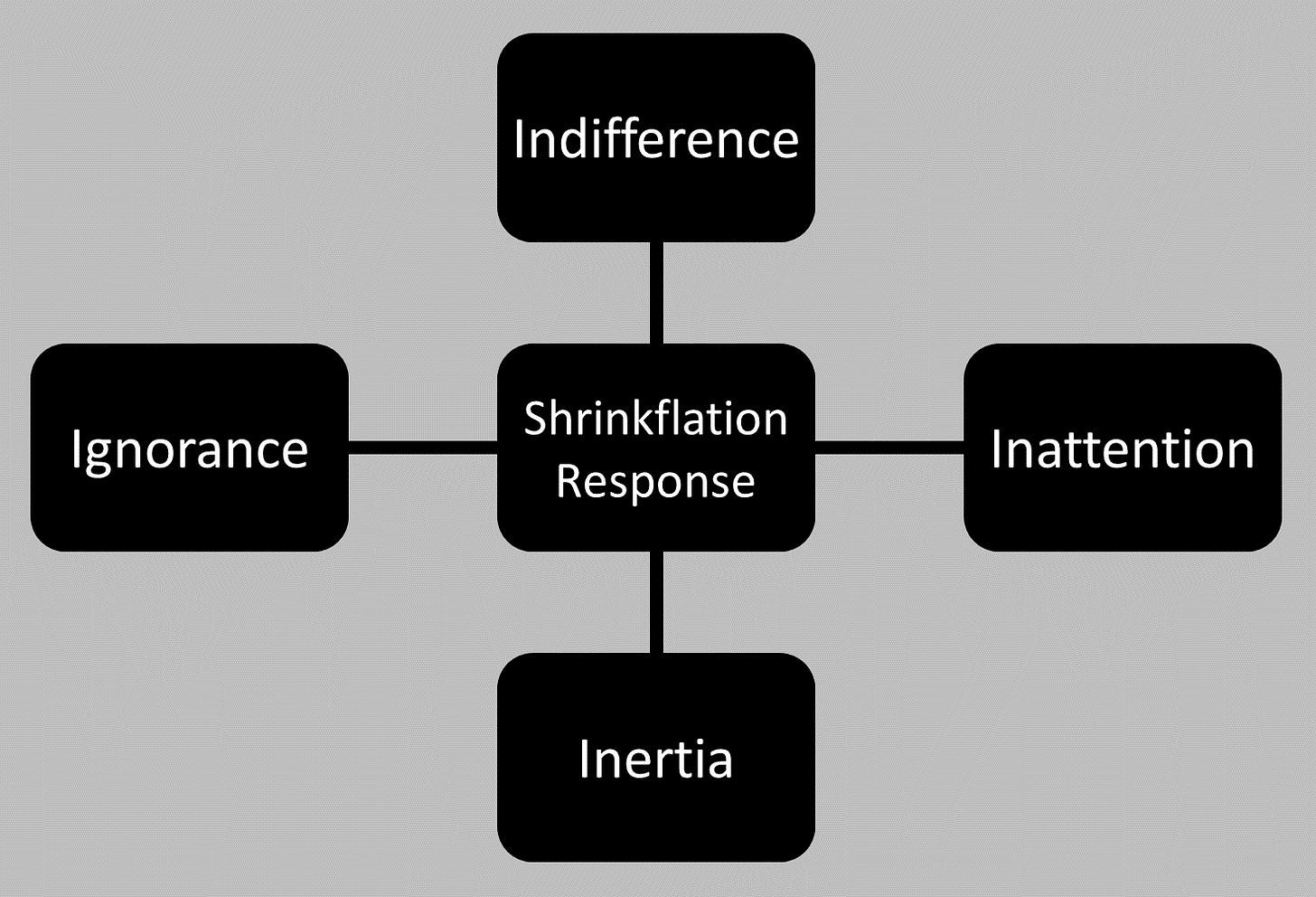

A framework of consumer response to shrinkflation based on indifference, inattention, ignorance, and inertia explains the effectiveness of shrinkflation.

Over the past three years, shrinkflation ― reducing an item’s quantity or weight while maintaining its price, has been widely used by brands, particularly for consumer packaged goods, to raise prices indirectly. Shrinkflation is effective because grocery shoppers are more sensitive to price changes than they are to changes in the amount or quantity, by as much as four times, according to one paper.

In this post, I want to explore (and correct) one common misunderstanding that many people have about shrinkflation and introduce an idea that I called the 4I Framework of Consumer Response to Shrinkflation to explain why shrinkflation is so effective for CPG products. I also have two specific recent examples that illustrate shrinkflation’s boundaries.

Shrinkflation is one component of a brand’s Price Pack Architecture

Many consumers, and even some managers, wrongly believe that shrinkflation is a stand-alone pricing strategy applied to individual items or SKUs. This is not the case. In CPG, shrinkflation is an integral part of so-called price pack architecture programs, where the brand uses a constantly evolving set of rule-based and experience-based practices to manage its product lines by adding, subtracting, and augmenting individual items in the line so as to maintain an overall attractive and coherent (feature-wise and price-wise) set of offers for its target consumers. Changes in SKU prices and quantities can go either way, higher or lower, and are routinely accompanied by packaging changes, such as subtly changing the shape, color, or materials used and adding or removing descriptions, taglines, and images, and less often by ingredient or formulation changes. As I have written in an earlier shrinkflation post on the Pricing Conundrum,

The ‘architecture’ in price pack architecture refers to the fact that there is a structure to how managers define and choose the different sizes, features, and prices, typically by conducting consumer research and examining the level of sales, consumer preferences, profitability, and so on. Inflation is just one factor in this decision-making and likely not the most crucial consideration.

In discussing Frito Lay’s product line strategy back in 2014 and 2015, its North America CEO Tom Greco provided the following explanation that captures the logic of price pack architecture from the perspective of CPG executives:

“First, on the consumer side, households were getting smaller. By the end of 2014, over 60% of U.S. households had two people or less, making a strong case for a smaller bag of take-home Lay’s. Meanwhile, our customers were facing huge margin pressures. In 2014, grocery margins had dipped over 40 basis points in just one year. And, finally, we knew that over 90% of Lay’s take-home business was in just one size. In fact, we had 14 s.k.u.s (stock-keeping units) of 10-oz Lay’s, and the majority of the transactions on this size were buy-one-get-one-free. As a result, we recently introduced a smaller 8-oz bag of Lay’s with full variety. We then reduced the lineup on our 10-oz bag and branded this ‘Family Size.’ Finally, we added weight to our largest size and branded this ‘Party Size.’”

In addition to this package juggling, the brand also stopped promoting all 14 SKUs using BOGO promotions, limiting such promotions to only 4 or 5 SKUs and only on specific holidays. They were raising prices in some instances and lowering prices in others depending on what shoppers bought, and always indirectly so that the price changes were not visible to the grocery shoppers. This mini case study illustrates the typical complexity and nuance involved in managing a price pack architecture.

Over the past two decades, before Covid, implementing an effective price pack architecture meant that as input costs fluctuated, so did quantity. Quantity decreased at times when input costs went up and increased when costs went down. For example, one British study conducted by the UK's Office for National Statistics in 2019 estimated that “between 1% and 2.1% of food products in [the] sample shrank in size, while between 0.3% and 0.7% got bigger." When the price did go up, it was often accompanied by noticeable improvements in the product. As P&G’s CFO Andre Schulten said in a recent conference call: “Every price increase or most price increases are connected to innovation, meaningful innovation for the consumer, that also guarantees retail support. They are [also] linked to strong value communication.”

To summarize, in the CPG space, price increases are rarely standalone, simple actions; it’s more accurate to think of them as offer-based tactics that change the nature of the value the product offers its consumers.

However, post-Covid, the shifts in CPG items’ quantity or amount have been in one direction. As input cost pressures have grown and grown with sustained inflation, so has the pressure to shrink packages and the amount in them while trying to maintain price. Price pack architecture decisions have mostly become shrinkflation decisions. Which begs the question, why has shrinkflation been so effective these last three years?

Consumers’ resistance to the idea of shrinkflation

Now, don’t get me wrong. When consumers are surveyed about shrinkflation, many express concern and say they intend to change their buying behavior in response. For example, a YouGov survey earlier this year reported that 73 percent of American consumers replied “very concerned” (41%) or “fairly concerned” (32%) when asked how concerned they were about shrinkflation.

Furthermore, a significant number, between 20% and 50% of these concerned respondents, reported noticing that shrinkflation had occurred in various CPG categories in the previous six months since September 2022. About half of all respondents in the YouGov survey indicated they would either switch to generic or private-label brands because of shrinkflation. It’s clear, and not surprising, that a majority of grocery shoppers are not thrilled with shrinkflation.

The four-I framework of consumer response to shrinkflation

Yet, indications are these assertions haven’t yet translated into significant changes in shopping behavior. Over 2022 and much of 2023, the major CPG brands have reported healthy profits, growing both their top lines and their bottom lines consistently quarter after quarter, even as inflation has continued to bite into their input costs. Thus, we have one of those conundrums that makes pricing strategy so interesting: Why has shrinkflation been so effective when it is shunned by everyone concerned, those who practice it, and those who are affected by it?

One reason is that most discussions of shrinkflation focus on the so-considered unfair practices of CPG brands or the buzzworthiness of social media posts that identify an instance of shrinkflation. However, they don’t give sufficient attention to the underlying consumer psychology that contributes to shrinkflation’s success. I ascribe these effects of consumer behavior to the four “I”s of grocery shoppers: Indifference, Inattention, Ignorance, and Inertia.

The four-I factors dominate grocery shopping psychology, and each one makes it really hard for shoppers even to identify that shrinkflation has occurred since their last shopping trip or purchase, let alone figure out its extent and exact impact on their wallets. When operating in tandem, the four-I factors make it really difficult for shrinkflation to impact shopper behavior and they insulate CPG brands. They also encourage shopper behaviors like curbside shopping, home delivery, and subscription-based top-ups of staples, which make it even harder for individual shoppers to identify or respond to shrinkflation. Let’s consider each of these four factors briefly here.

Indifference. When it comes to making choices in grocery stores, a significant fraction of consumers is indifferent in many categories, ready to switch, and lacking particularly strong preferences. For example, one 2021 eMarketer study reported that 80% of grocery shoppers purchased a different brand from the one they usually purchased that summer. An earlier study concluded that “Loyalty erosion and consumer defection are pervasive and costly problems for CPG brands, and their impact is increasing dramatically in the current economy.” The consumer decision making behind a lot of grocery store shopping is limited problem-solving or habitual response, based on limited information processing, and subject to flexible or poorly-formed preferences.

Inattention. A core characteristic of limited information processing and habitual buying is the lack of attention to information cues. Hard as it is for many CPG brand marketers to admit it, few grocery store shoppers pay careful attention to the information presented to them on store shelves or on packages. Things like nutrition labels, health information, and, for our purposes, information about quantity or amount matters, but only to a very small fraction of shoppers. Most shoppers are not attending to specific details of items in their shopping cart from one trip to the next and are not sensitive to minor changes in them.

Ignorance. The ignorance here refers to ignorance about prices. The fact that grocery shoppers have poor price knowledge has been established over and over, starting with the classic Gabor and Granger (1961) paper to the well-cited Dickson and Sawyer (1990) and Vanhuele and Dreze (2002) papers. This poor knowledge about grocery prices extends to related domain knowledge, such as the impact of inflation on prices. As an example, one recent survey conducted by PYMNTS in September 2023 found a distorted view of inflation among shoppers. Respondents estimated that grocery stores had increased prices by 23.2% over the past year when, in reality, prices had increased 24.5% over the past three years. The obvious implication of poor price and price change understanding is that shrinkflation is hard to identify or assess.

Inertia. Habitual buying is rampant in groceries. While this might seem like a conflict with the indifference of grocery shoppers at first glance, it is not. Inertia, in this context, means a sense of low-involvement and repetitive buying of the same items even when there is no psychological attachment to particular brands. For instance, I may buy a tub of Chobani yogurt, a block of Tillamook sharp cheddar cheese, and a DiGiorno pepperoni frozen pizza because I consume these things regularly without caring all that much about these particular brands. We can call this inertial buying because although it looks like loyal buying, it is simply repetitive, disengaged buying. Habitual purchasing discourages attention on specific cues, including prices, amounts, and changes in them, and facilitates shrinkflation.

Two cases demonstrating the boundaries of four-I supported Shrinkflation

The four-I theory implies that external or contextual factors that modify normal consumer behavior from its relatively uninvolved, inattentive, apathetic state into a more attentive, engaged mode will lead consumers to notice and respond vigorously to shrinkflation and reduce the scope and efficacy of this pricing strategy, and may even make it extremely undesirable to use for CPG brands. Here are two cases that illustrate when this might happen, although they are very recent and the outcomes are still in flux.

Betty Crocker Cake Mix. The first case is about the recent shrinkflation in a Betty Crocker white cake mix, from 16.25 oz. to 14.25 oz. It turns out that this cake mix is used not only by home bakers but also by many professional bakers (including Crumbl Cookies, according to its eagle-eyed customers) to create the base layers for their creations. Since cake recipes call for precise quantities of ingredients, and professional bakers, in particular, tend to adhere to these quantities religiously, the reduced quantity in the Betty Crocker cake mix was noticed immediately, and created a furor. More importantly, it caused the professional bakers using this product to behave differently, although the upshot of this behavioral change is up in the air. The video below describes the current situation through the eyes of a professional baker experiencing Betty Crocker’s shrinkflation.

Oreo Cookies. The second case is about Oreo cookies. As a CPG brand, it falls on the iconic end of the brand value spectrum, with a long heritage and a gigantic, core fan base that would score very low on every one of the four Is. In other words, they are engaged, loyal, and pay attention to anything involving the cookies. The most recent shrinkflation-related controversy sparked on social media within the past week is about whether the amount of creme filling in Oreos and Double Stuf Oreos has been reduced by its parent company, Mondalez.

Many loyal fans complained about noticing this reduction independently on various social media platforms and chatrooms in vivid terms. Mondelez responded quickly and pushed back, with its CEO asserting that the brand “hasn’t messed with the cookie-to-creme ratio” because “we would be shooting ourselves in the foot if we would start to play around with the quality.” In trying to settle this dispute, third-party experts have concluded that the nutritional and weight information on Oreo’s packages indicates no shrinkflation and any perceived creme paucity may be simply because of normal manufacturing fluctuations. The Oreos loyalists are not buying it. How this will turn out is anyone’s guess, but is clear that a potential change is shopper behavior is on the cards.

Both cases illustrate that whatever the underlying reason (and it could vary by context), when grocery shoppers break the shackles of the four-I factors, they notice even a trace of shrinkflation and respond vigorously, verbally and through their actions. Shrinkflation works so well because they rarely do.