On the Usefulness of Distinguishing Purchases from Investments

Conflating the two concepts confuses the nature of value derived from products and experiences, leading to unreasonable expectations and poor choices.

The American investor Barbara Corcoran tells the compelling story of how her purchase of an expensive wool coat when she was starting out changed her life and was “the best investment I ever made.” In her early twenties, she had started working in real estate sales. When she took clients out to viewings, she wore an old, low-end pea coat. According to her, the shabby coat failed to convey an image of a successful, competent realtor to herself or to her clients and set her back. When she purchased the $2,300 (in today’s dollars) Bergdorf Goodman wool coat and started wearing it, however, it gave her a confidence boost, changing her image about who she was and what she wanted to accomplish. In her words, the coat “made me feel just like the big deal I hoped to become…In my coat, I worked like crazy to become as successful as I looked.”

Like Ms. Corcoran, we often think of major, and sometimes even minor, purchases as investments. When assessing the value of objects and experiences, a framing approach that many buyers adopt is viewing an item as an investment instead of a purchase. In our everyday conversations, we routinely say things like, “You should invest in a good pair of shoes,” or “My car has turned out to be a great investment.” But is this a good way to think about these products?

In this post, I want to consider how thinking of goods and experiences as investments instead of purchases — whether it is a pair of shoes, a vintage mechanical watch, a trip abroad, or even one’s home, can potentially harm us as consumers. The main argument I am going to develop is that it is best to keep purchases of consumer goods or services, no matter how valuable, resalable, appreciating in value, or life-changing they may be, separate from investments and think of them as possessions instead.

N. C. Wyeth’s Ramona

Two stories about the pricing of artwork that were in the news recently will help us to begin untangling the differences between purchases and investments. The first story was about a lucky thrift shop purchase. Back in 2017, a shopper was hobby-browsing in a New Hampshire thrift shop, looking for frames to restore and reuse for paintings. She was searching through a stack of old frames with posters and prints in the shop and came across a heavy, dusty framed painting. She liked its white frame more than the painting itself (see below to see if you agree) and purchased it for its tagged price of $4. Then, as Lawson-Tancred tells it:

“After she did some brief research online and failed to identify the work, she stored it in a closet. There, it was quickly forgotten about until May of this year, when the woman stumbled across the painting during a spring clean and decided to post the work on the Facebook group ‘Things Found in Walls.’ Soon enough, she was connected with Lauren Lewis, an art conservator based in Maine, whose excitement seemed to suggest she may have been accidentally storing something special. It quickly became clear that the simple frame was of much lesser value than the striking scene within, which was revealed to be by the renowned painter and illustrator N.C. Wyeth.”

The painting turned out to be an “excellent example of Wyeth’s sensitive and stylish interpretations of literary work,” one of a set of four frontispiece illustrations for a novel called Ramona. The piece sold at a Bonhams auction in September 2023 for $191,000. The charity shop buyer earned around $150,000 after accounting for the buyer’s premium markup. The anonymous shopper’s $4 Wyeth’s Ramona painting purchase turned into an inadvertent gain of $150,000.

The Sinking Value of Bored Apes

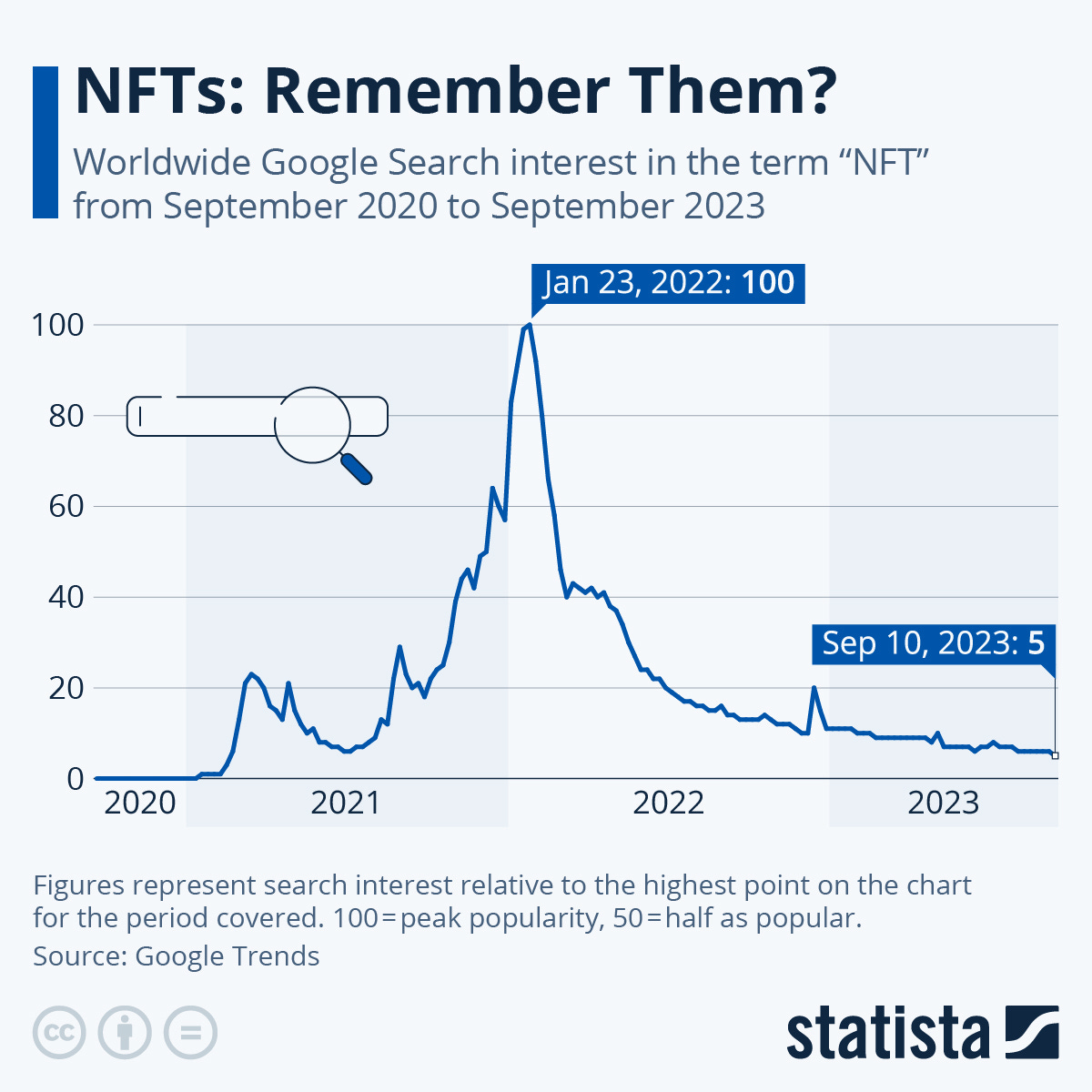

The second artwork pricing story in the news recently was about something that was inescapable in 2021 and 2022 but which has dwindled out of our collective consciousness this year: the digital artworks known as non-fungible tokens or NFTs. To remind you, NFTs provide certification of digital ownership and have been especially popular for digital artworks like Beeple’s famous Everydays: The First 5,000 Days, which sold in a Christie’s auction for a cool $69.3 million back in March 2021, the Bored Apes Yacht Club collection and the CryptoPunks collection, among many others.

During their heyday in 2021 and 2022, there was a “Niftymania” as more and more speculators, many of them with wallets fattened by gigantic cryptocurrency gains, jumped into the NFT market to buy up any and all available NFTs as lucrative investments, and then resell the artworks within days or weeks for staggering profits. I said in a CBC interview at the time that:

“If you think of this as a game of musical chairs, we are in the middle of the game, and everyone is doing really well. So the game will continue on until someone is left out at the end.”

Well, the musical chairs have come to an end, and many NFT investors have been left without chairs. The recent headline that stirred up a lot of media interest was about a study by dappGambl of the current prices in the NFT digital art marketplace. It said, “95% of the digital collectibles may now be worthless.” There are a lot of interesting findings in dappGambl’s study, but the main one reported by dappGambl is as follows:

“We have compiled a comprehensive analysis of over 73 thousand NFT collections (73,257, to be exact) in order to identify key trends, assess the health of the market, determine the factors contributing to successful projects, and hopefully gain insights into the potential future trajectory of the NFT ecosystem…Of the 73,257 NFT collections we identified, an eye-watering 69,795 of them have a market cap of 0 Ether (ETH). This statistic effectively means that 95% of people holding NFT collections are currently holding onto worthless investments. Having looked into those figures, we would estimate that 95% to include over 23 million people whose investments are now worthless.”

Relatively speaking, the Bored Ape Yacht Club (BAYC) NFTs, which were among the most popular ones on the market, have done better. Someone buying a BAYC NFT at its peak in April 2022 would have paid an average of 153.7 Ether, corresponding to $430,000 (with highs reaching $3.4 million). However, if you want to buy a BAYC NFT today, you would pay 26.7 Ether on average, or about $42,500. Essentially, the NFT buyer’s BAYC investment of $430,000 turned into $42,500 and is still going down.

The Motivations and Mechanisms of Value Delivery for Purchases and Investments

In comparing these two stories, one thing is clear: from the perspective of the buyers involved, the N.C. Wyeth Ramona painting was a purchase, while the acquisitions of BAYC NFTs were, and still are, invariably investments; the underlying motives and expectations of the buyers were fundamentally different in the two situations.

We can imagine the anonymous shopper walking into the New Hampshire thrift store, intent on buying a frame to serve a specific functional end. She wanted a vintage picture frame to frame a painting and sought out a thrift store to search for affordable options. Thrift stores serve dual purposes for shoppers. First, they are places to find functional or decorative, typically used, and often old items for really good prices. Second, there’s an element of treasure hunting involved, where browsing through the store, one could stumble across something unexpected and wonderful, and perhaps even valuable, at any time.

With both buyer motives, the underlying mechanism is one supporting purchase, where the buyer seeks to extract a constellation of benefits — functional, emotional, social, and psychological, from the purchase experience and its subsequent use over a lengthy period. No one walks into a thrift store thinking, “Today is the day I take the first step towards becoming the next Warren Buffet by investing in an antique vase.”

Investments, on the other hand, have completely different motives and mechanisms of value delivery to the investor. The primary purpose of an investment is to produce income or wealth (depending on how big and how good the investment is) at some point in the future. Investments provide virtually no use value to the buyer, none of the functional, emotional, social, or psychological benefits that purchases and possessions deliver. A mutual fund in my retirement account may give me money to spend when I retire, but it doesn’t make my dinner taste good or look good on my wall to impress people in Zoom calls.

A rental property is an excellent example of an investment. When someone buys and owns a rental property, their role is one of a rent-extractor and investor, distinct from a homeowner. Their primary motive is to earn rent, and consequently, the property’s upkeep and improvement, even when it involves decoration (e.g., furnishing an Airbnb rental), is evaluated through the lens of the return on investment. Even though the rental property is technically purchased, say with a mortgage, the value it delivers is economic and economic alone. It is an investment.

In the same way, when people purchased NFTs enthusiastically over the past couple of years, they were not interested in looking admiringly at the Gordon Goner Ape on their laptop screen every day and marveling at the artist’s skill and creativity. (They could’ve done that anyway since these images are readily available to view online). They were solely focused on the future value of these artworks and were expecting and hoping that the value would go up substantially so they could sell at a higher price and earn a profit. For buyers, a Bored Ape NFT was no different than NVIDIA stock or a three-month treasury bill.

The problems with conflating purchases and investments

So far, I have argued that a purchase provides a constellation of functional, emotional, social, and psychological benefits to the buyer, while an investment provides economic benefits only. Now, I want to develop the idea that conflating purchases and investments often leads to negative financial outcomes for the buyer, along with unreasonable expectations and poor choices.

Negative financial outcomes

First, purchases of consumer goods blended with investments rarely deliver positive financial outcomes1, even when the buyer intends to profit from the purchase. Ms. Corcoran’s successful use of an expensive wool coat as the foundation to build a stellar career is an exception not the rule. Just think of the countless people who’ve bought equally or more expensive coats, shoes, watches, and other luxury items at Bergdorf Goodman and elsewhere to boost confidence, feel good, burnish their personal brand, or rise to the top, and haven’t become real estate moguls, investment bankers, or CEOs. For all these non-Barbara Corcorans, they just spent a lot of money on pricey whatnots that are sitting in their closets. It’s far more likely that shoppers will deplete their savings or fall into debt in their quest for sartorial investing than they will rise to the top of their professions.

Objects like expensive clothes or fancy cars may help certain professional endeavors at the margin, but factors such as skills, resilience, work ethic, and other individual characteristics are far more important. This is also true of other possessions. As an example, a majority of Americans think of home ownership as an investment. Atlantic reporter Jerusalem Desmus summarizes this perspective:

Homeownership is a guarantee against a lost job, against rising rents, against a medical emergency. It is a promise to your children that you can pay for college or a wedding or that you can help them one day join you in the vaunted halls of the ownership society. In America, homeownership is not just owning a dwelling and the land it resides on; it is a piggy bank.

Yet, such a perspective ignores the risk inherent in owning a home and the difficulty of reliably extracting income from it. It also ignores the fact that for most homeowners, their home does not turn out to be a good investment. As Joe Cortright puts it:

“If you buy at the wrong time, if you buy in the wrong place, if you pay too much for the money you borrow and don’t have the financial wherewithal to weather economic turbulence, chances are that home ownership could turn out to be a wealth-destroying, not a wealth-building, proposition.”

Unreasonable expectations and poor choices

When people make a purchase with the view that it will generate a financial return directly or indirectly, they give weight to the wrong product features, become overly optimistic about the future, and often end up overspending. For instance, if you believe that your house is an investment and will generate a healthy return, then the conventional advice given by realtors and mortgage bankers that you should buy “as much house as you can afford rather than buying small with a plan to move up” makes sense.

With an investment mindset, you are likely to think more about how much the house will appreciate and sell for in the future and less about whether you’d like living in it now, how much it will cost each year to own, and how much functional, emotional, and psychological benefits it will provide as you live in it. Then, as real estate prices go down or the market seizes up as it tends to do from time to time and its investment potential becomes shaky, your house will cause you disappointment, frustration, and a host of other emotions instead of pleasure and enjoyment.

The same is true of everything from rare watches, luxury handbags, and shoes to wine, artwork, or virtually any product, service, or experience you can think of. Bringing future financial value into the equation dilutes the significance of the essential benefits that our possessions are supposed to give us.

There’s a saying in my native Gujarati language that roughly translates like this: The washerman’s dog lives his life in limbo because he belongs fully neither to the house nor to the laundry shop. The same is true of our purchases when we treat them as investments. They become neither good investments nor good possessions, failing to deliver financial returns or enjoyment adequately. The best approach is to keep the two separate.

One point worth noting here is that there are established and well-functioning markets for specific consumer goods like limited-edition sneakers (StockX), fine wine (Cellaraiders), and watches (Chrono24) that allow consumer goods to be bought and sold just like investments. However, because of the variety, rarity, and fragmentation of buyers and sellers, it is questionable to what extent investors participating regularly on these exchanges earn a good return on a consistent basis.