Pricing Case Study: The Moonswatch Success Story (plus a Typology of Collabs)

With the growing popularity of asymmetric brand collabs, we explore the logic, economics & business strategy behind the Moonswatch collab.

“History is repeating itself 40 years later, but in reverse.” - Oliver Mueller, LuxeConsult.

“Drop culture officially hit the watch world.” - Danny Milton, Hodinkee.

When the Swatch boutique in Lucerne, Switzerland, opened on Saturday, September 9, 2023, the line was over a hundred long and growing. The excitement level was similar to when people used to queue for two or three days outside Apple stores for the next-gen iPhone or for the Louis Vuitton - Supreme collab launch in 2017. This time, they were waiting for the Blancpain X Swatch Scuba Fifty Fathoms collab to drop. The scene was repeated at Swatch boutiques across the world, a welcome occurrence for an otherwise mature mass-market brand that many consider past its prime.

At first blush, the collab between two seemingly incongruous watch brands, one that makes mostly plastic watches and the other that makes handcrafted watches costing an average of $11,000, seems strange. But the high level of consumer interest suggests this collab will be successful. There’s another, more concrete reason to be optimistic about the Blancpain X Swatch release: it is building on a similar collab that has already become the biggest 2022 success story in the watch industry: the Moonswatch.

The MoonSwatch collab between Swatch and Omega was no less incongruous and far riskier because it was a “first” in the industry. It’s true that both brands belong to the same parent company (as does Blancpain), but Swatch is a decidedly mass-market, fifty-year-old brand. Omega, however, is an ultra-luxury Swiss watch brand with a history dating back to 1848. Its watches have been to the moon and are worn by countless celebrities and business titans (George Clooney and Prince William are said to be Omega loyalists). Its Speedmaster Pro, known as the Moonwatch, literally saved the Apollo 13 astronauts.

It’s like Walmart and Tiffany joining forces to sell an engagement ring. But that’s what happened. In March 2022, Swatch and Omega jointly launched the Bioceramic Moonswatch collection with this announcement:

“Swatch has collaborated with Omega to imagine an innovative Swatch take on the Speedmaster Moonwatch. The unexpected, provocative and visionary partnership, a first between Swatch and Omega, is the culmination of a trend of collaborations between luxury and street brands to create innovative new products that blend the best of both worlds. The brands have drawn their design inspiration from space, to create a collection of eleven Swatch models named after planetary bodies, from the giant star at the centre of the solar system to the dwarf planet at its periphery.”

The Popularity of Asymmetric Collabs

Asymmetric collabs between seemingly incongruous brands have taken off in recent years. We can define an asymmetric collab as “a marketing collaboration between brands having dramatically different prestige images.” Most involve an ultra-luxury brand and a mass-market brand. (There are other types of collabs. Many are quite conventional and have been around for decades, more on them later).

The asymmetric collab that paved the way for Moonswatch was the 2017 collab between the streetwear brand Supreme and luxury brand Louis Vuitton. This was followed by numerous collabs involving luxury brands like Prada, Gucci, and Dior and mass market brands like Nike, North Face, and New Balance. These collabs are typically one-off affairs where a line of products developed jointly by both brands with identifiable characteristics of each one are sold for a short period through special channels like pop-up stores or online drops. Their main goal is to generate hype and excitement in both customer bases, drawing temporary attention in a crowded marketplace.

However, the Moonswatch collection is different. Swatch and Omega have stated that they plan to keep making and selling the entire line of Moonswatches as long as there is consumer interest. In their most recent missive to customers, the two brands were explicit about the non-limited time nature of Moonswatches (perhaps to reduce flipping activity).

“We’re working around the clock behind the scenes to make the 11 unique watches and are replenishing our selected Swatch stores regularly with this special collaborative collection between Swatch and OMEGA. While these are definitely special, they aren’t part of a limited edition, so you should indeed be able to get your hands on one.”

As noted, although the two brands are owned by the same parent company, there is virtually no overlap in target customers, product quality, price points, or brand image between them. Omega dominates Swatch in every respect. Omega’s Moonwatch line starts at around $5,250, whereas the average Swatch price is $200-3001. An Omega is a buy-for-life, heirloom watch; A Swatch is a disposable, “just for fun” watch, like Ikea furniture. As Worn & Wound put it:

One known for accessibility, irreverence, and color (and saving the Swiss watch industry), the other for luxury, quality, and perhaps the most iconic watch ever produced. A watch that is synonymous with one of humankind’s greatest achievements. An achievement that loses none of its mystique as decades pass. Landing on the Moon.

In an asymmetric collab, the potential benefits to the mass-market brand are obvious. With every Moonswatch sale, Swatch will soak up the reflected glory of Omega’s stellar (lunar, really) reputation and shine a little brighter. As brand marketers know all too well, this will deliver serious future benefits.

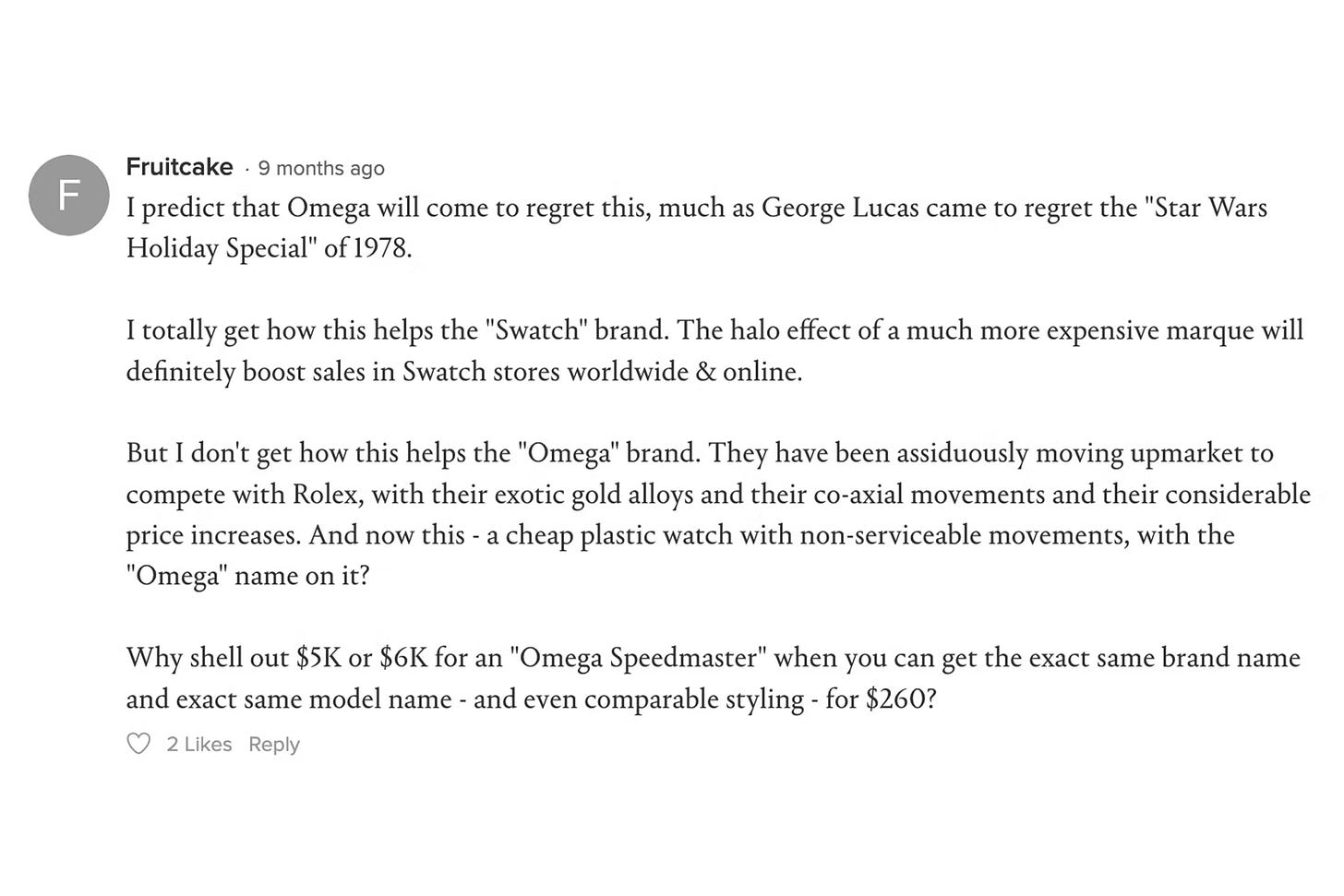

The benefits to Omega are less clear. In fact, using a Good-Better-Best (GBB) framework, we can argue that getting buyers to “trade down” behaviorally by buying $270 (originally $260) watches and conceptually through associating Omega with an unmistakably cheaper, less durable offering should be something that the luxury brand marketer would want to shy away from. With the collab, Omega’s now implicitly endorsing a $270 substitute for its $6,000 Moonwatch. A poster on a Hodinkee message board summarized this risk nicely:

The negative impact on Omega could be long-lasting or even permanent. As Mark Ritson put it:

“The obvious criticism for the project is that it could easily undermine the Omega Speedmaster for a very long time. On Saturday, no matter how quickly Swatch closed its boutiques, it almost certainly sold more Moonswatches in one morning than Omega will sell Speedmasters all year. That’s a scary statistic given just how similar the two watches look up close, never mind from the discrete distance behind a long sleeve shirt.

Shortly after the Moonswatch collab was announced in March 2022, a journalist asked 18 CEOs of rival watch companies what they thought about it. 17 CEOs thought it was “an appalling idea that would devalue the brand, put off serious watch collectors, and generally make a mockery of a watch unanimously agreed to be a classic of 20th-century design”

Given the unanimous pessimism based on obvious and potentially serious risks, what’s in it for Omega? And more broadly speaking, why would ultra-luxury brands like Omega, Blancpain, and Louis Vuitton, which are already in great demand with waiting lists for their products, want to undertake collabs with downmarket brands?

These are important questions given how quickly asymmetric collabs have spread since Covid. To answer them, we need a rigorous understanding of the types of collabs that exist in the marketplace and the logic behind them.

A Framework for Evaluating Collabs

Collabs are a modern spin on an old, tried-and-tested marketing program. What millennials and Gen-Z marketers call a collab was variously called co-branding, a brand alliance, joint marketing, or symbiotic marketing by boomers and Gen-Xers ten, twenty, or thirty years ago. Back in 2002, Abratt Russell and Patience Motlana defined co-branding as:

“the long- or short-term association or combination of two or more individual brands, products, or other proprietary distinctive assets to form a separate or unique product. The brands can then be represented physically or symbolically through the association of brand names, logos, or other proprietary assets of the composite brand.”

Product and image synergy. Although it’s rather wordy, the definition still works nicely in 2022 to describe a collab. One interesting academic finding about collabs is that it is really hard to predict which collab will work and which won’t in advance. One reason for this “variability of outcomes” is that collabs are of different types, each involving different partners and goals.

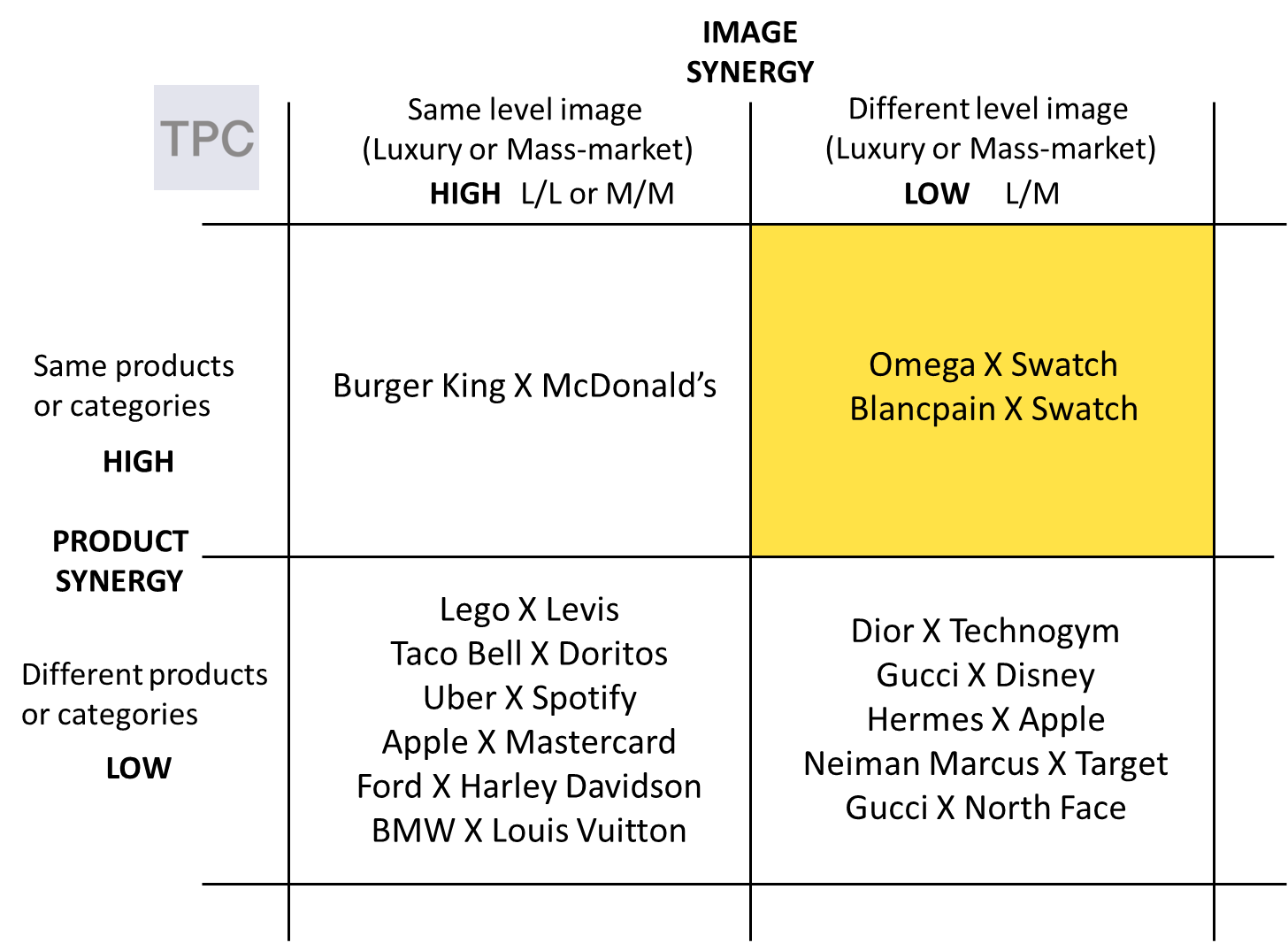

So it makes sense to explore the different types of collabs and understand the differences. While there are other ways of classification, I use the concepts of product synergy and image synergy in this post. Product synergy refers to the degree to which the two collaborating brands sell the same products or categories. Image synergy is about whether the two brands target the same market (luxury or mass-market) or different ones. The figure below shows examples of the four types of collabs by crossing product synergy and image synergy.

High image synergy, low product synergy (Bottom-left quadrant)

Most collabs occur between brands that are similar in image but sell different products or categories. Mass-market brands prefer to collaborate with other mass-market brands, and luxury brands tend to collaborate with other luxury brands.

The Taco Bell-Doritos collab is a typical example. Back in 2012, Taco Bell introduced a new taco called the Doritos Locos Taco, using a shell made from Doritos. (I recommend it, it’s delicious!) Both are mass-market brands selling different food categories (packed CPG vs. fast-food restaurant) to younger, price-conscious consumers who want cheap, tasty eats. The idea behind the collab was to get a greater “share of stomach” of the partner’s large, loyal customer base, with the implicit understanding that there was lots of stomach space available to share.

This simple logic made it a strong win-win. Taco Bell won by generating buzz for the offering, bringing Doritos fans into their stores, and selling other products (and high-margin soft drinks) to them. Doritos won by generating new sales for its otherwise slow-growth product in a new market. Not surprisingly, a decade later, the collab is still going strong.

Low image synergy, low product synergy (Bottom-right quadrant)

Collabs between luxury and mass-market brands selling different products are far less common and typically involve ultra-luxury fashion labels who want access to new customers. The mass-market brand benefits through its association with luxury. Neither brand has to worry about cannibalization because they sell different products.

The 2015 collab between Apple and Hermès is a good example. It involved Apple watches branded with the Hermès logo and specialty straps like the double-tour, sold at a premium price. Although Apple caters to the mass market in the conventional sense, both are market leaders and A-listers in their respective categories. Each brand exchanged cachet with the other through the collab. Hermès modernized its brand by stamping its name on a top-tier, high-tech product it could never have made itself. Apple benefited from injecting Hermès’ luxury aura into its “best” (in a GBB sense) high-margin watch, sharing affluent shoppers’ wrists and watch cases with Rolex and Audemars Piguet.

High image synergy, high product synergy (Top-left quadrant)

Of the four quadrants, this is the most intriguing but also the most sparsely populated quadrant. Essentially, this type of (mostly hypothetical) collab involves two direct competitors - same image, same products - collaborating (or trying to collaborate). In 2015, Burger King proposed “merging” with McDonald’s for just one day to offer a sandwich called the McWhopper.

On a fully functional (now defunct) website, it laid out its marketing plan. The proposal was for BK and MCD to come together on Peace Day, September 21, and offer a hybrid product containing “the best of both sandwiches” at a single location in Atlanta to generate publicity for the cause (and, presumably, for themselves). Not surprisingly, the BK proposal generated tremendous excitement on social media. However, McDonald’s declined, and the collab never happened. As in this case, these collabs are likely to be PR stunts or acts of one-upmanship.

High image synergy, high product synergy (Top-left quadrant)

Collabs in this quadrant, where the Moonswatch falls, occur between a luxury brand and a mass-market brand selling the same products. As mentioned earlier, this is the riskiest type of collab for both parties, with uncertain payoffs. For the luxury brand, such a collab can dilute its exclusive and high-status image, ultimately resulting in the loss of pricing power and rejection of its core products by its core customers. For the mass-market brand, the collab can shine a light on the relatively poor quality of its core products.

A lot can go wrong in such collabs. Yet, eighteen months after launch, the Moonswatch collab has been tremendously successful, as the video describes. Next, we will consider why.

The Moonswatch Collab Strategy2

The Moonswatch collab should’ve failed. Indeed, it was expected to fail by virtually all experts. Yet it was, and still is massively successful. The reasons why is the story of a series of deliberate, counterintuitive, and synergistic strategic activities undertaken by the Swatch Group, the parent company of Swatch and Omega. The company orchestrated every aspect carefully before, during, and after the launch of the Moonswatch line. Learning about the decisions it made provides lessons not only about how to make asymmetric collabs work but also about how to manage brand growth effectively.

A disruptive, risk-on mindset from the outset: Data-driven marketers won’t like this, but the Swatch Group did not rely on any market research or use any templates of previous collabs for this project. The collab’s leaders, including Swatch Group’s CEO, “were guided in equal part by the heart and by the head. Passion and joie de vivre were key. Emotion at the service of rationality. Instinct that threw away the rulebook.” They used their collective expertise and intuition to come up with the idea for the Moonswatch.

Watches used a new material. The company leveraged an existing innovation serendipitously. It had discovered a new material called bioceramic, a blend of ceramic and plastic, and was intent on using it for one or more of its products. They landed on Moonswatch as the launch vehicle. It became the first watch to be made with bioceramic. The material imparted resilience and luster to the watches and allowed new colors, giving Moonswatches a distinctive appearance, unlike any other Swatches or Omega pieces (or other watches, for that matter).

Painstaking attention to design. Each component of every Moonswatch in the line was designed carefully, with homage to the design elements of the original Speedmaster Pro. The designers and engineers put a lot of work into each model. They drew upon specific elements from various Omega watches for each Moonswatch. For example, the red case and the seconds hand of the Mission to Mars watch were borrowed from a 2008 limited edition Omega Speedmaster called the Alaska Project.

Taking control away from collaborating brands. Counterintuitively, instead of the two brands’ managers, the parent group’s executives controlled every aspect of the design, manufacture, and launch strategy. Few managers at Swatch or Omega even knew about the project; only selected individuals were included for specific contributions to design, development, and marketing. The centralized decision making eliminated potential turf wars and conflicts.

Very tight timeline to launch. The collab’s original plan was to introduce the Moonwatch in May 2022 during a lunar eclipse. However, to reduce the risk of leaks and to generate surprise and buzz, it was moved forward by two months, to March 2022, a few days before a major watch convention. The tight timeline focused everyone’s efforts and minimized evolving conflicts.

In-house manufacturing. All manufacturing was done in-house using proprietary technology in plants owned by ETA, a subsidiary of the parent company. The tight timeline meant that numerous manufacturing decisions (e.g., eight different hand shapes with different finishes, using brass typically limited to higher-priced watches) were made and executed quickly.

Distribution only through Swatch Boutiques. Rejecting online sales, the company chose to launch the watches only through 110 Swatch boutiques (out of 168), which had an Omega boutique nearby. The Omega stores displayed the Moonswatches but didn’t sell them, strengthening the connection between the two brands. The company called it a “selective distribution strategy for an inclusive collection.”

Non-limited in time or quantity. Both brands publicized the fact that the Moonswatch collab was not limited but a longer-term offering that would remain available for years. This separated it conceptually from the typical asymmetric streetwear collab and also served to dampen some of the speculative buying for flipping purposes. (However, the watches still sell at a healthy premium on eBay).

An accessible, simple price point. The line was launched at a price of 250 Swiss francs ($260), which was the higher end of Swatch prices and much lower in price than anything Omega sold. While not quite iconic, the simple price is consistent with Swatch’s price image.

Social media-friendly launch. No one knew what the watches looked like until a few days before launch. Well-timed teaser ads a few days before release further raised anticipation levels. Watches were delivered to the Swatch boutiques in closed suitcases with great fanfare that could only be opened on launch day and were in short supply. (They still are). These ploys generated tremendous interest and enthusiasm, with shoppers lining up for two or three days prior to launch and visiting Swatch stores over and over to build their collection (or flip on eBay).

Results of the Moonswatch Collab

When Swatch launched in 1983, the Swiss watch industry was in the doldrums, plagued by fierce competition from Asian brands like Seiko, Citizen, and Casio and a steady decline in consumer interest. Over the next decade, Swatch used a breakaway positioning strategy to change the way mass-market consumers thought of watches. Instead of functional jewelry that is expensive and durable, Swatch created the idea of “watches as fashion accessories,” something that is cheap and fun, bought impulsively and discarded after a while. This conceptual product transformation turned around the fortunes of the moribund Swiss watch industry.

Today, the tables have turned 180 degrees. Swatch has been struggling for a number of years, and ultra-luxury brands like Omega and Blancpain have never been stronger or more coveted by watch enthusiasts and affluent consumers all over the world. In light of these changed circumstances, how did the Moonswatch fare for the two collaborators? Let’s consider what we know about some of the key performance metrics from public sources.

Unit sales. The company sold over one million Moonswatches in 2022, and its halo carried over to other Swatch products. For instance, three months post-launch, one report indicated sales of other Swatches (not Moonswatches) were up 41% in Switzerland. The company earned an estimated revenue of over $275 million from Moonswatch sales, enjoying a gross margin of 90%3. Omega also benefited tremendously from the exposure. Sales of the entire Speedmaster line increased by 50% globally after the launch in Omega stores and by 40% on resale site Chrono24.

Brand image. The Moonswatch’s success boosted the Swatch brand. After years of languishing sales and diminishing perceptions, Swatch was again seen as a high-quality brand by many consumers, including a new generation, and spoken of in the same breath as its luxurious cousins. Interestingly, Omega also benefited, first by receiving attention from consumers who had never heard of the Moonwatch or the compelling story behind how it contributed to the Apollo 13 mission’s success. The fears about brand dilution did not come to pass.

Innovation. Motivated by Moonswatch’s success, Omega introduced two high-end versions of its flagship Moonwatch Professional watch in 2022, with many “world-first” components. These watches cost approximately $600,000, the very high end of the brand’s product line. This further burnished Omega’s brand and carried over to the Moonswatch.

Store traffic. On the day Moonswatch launched, buyers clamored outside every Swatch boutique, buying out stock within hours, if not minutes. Police had to be enlisted at the New York store to quell riotous crowds. In the weeks and months after, foot traffic in Swatch boutiques increased significantly as customers returned over and over again to get their hands on watches that were often out of stock. Omega boutiques also experienced significantly greater foot traffic, mostly from new, younger consumers who came to know about its history and pedigree.

Attractiveness as a retail tenant. The cachet of the Swatch boutique shot up, with commercial landlords lobbying for Swatch to open locations alongside other high-profile luxury brands. While Omega stores didn’t have the same degree of exposure, Omega is already a well-established luxury brand and a highly desirable tenant.

Media visibility. Due to the clever, attention-grabbing launch and the overall quality of the product line, there were headline stories in media around the world about the launch and the products. Social media mentions shot through the roof, and engagement in regular and social media has continued unabated, with stories still appearing every week, eighteen months later.

Pricing power. Each Moonswatch cost $260 (250 CHF) at launch. Secondary market prices shot up to as much as $4,000 within a few days. They have come down significantly since but still sell for $400 to $500 apiece (a 50% to 80% premium). For Omega, the entry-level Moonwatch is priced at $5,250, and its price goes up to $8,000. As more units of both brands sell post-Moonswatch, pricing power remains high.

Final assessment. None of the adverse outcomes feared by experts came to pass. Eighteen months on, the Moonswatch collab has been a resounding success along every dimension. It revived the fortunes of Swatch, much like Swatch revived the fading Swiss watch industry in the 1980s. In its 2022 Annual Report, the Swatch Group gave this bullish, emotional assessment:

“It has to be said that this launch was a win-win to the power of ten for Swatch, for Omega, for Swatch Group, for the company's production apparatus, for Swiss watchmaking as a whole, for luxury, for entry-level watches in particular, for watchmaking volumes and, last but not least, for the reputation and desirability of Swiss-made watches, especially among the younger generation.”

How should the customer see the Moonswatch collab? In one sense, collabs like the Moonswatch and last week’s Fifty Fathoms can be seen as democratizing Swiss watches, helping to blur the boundaries between brands of starkly different image levels. As Swatch Group’s CEO put it, “The exclusivity of brands [like Omega and Blancpain] cannot be the message. That’s not my message.” On another, more individualistic level, such collabs provide tangible access to products that most mass-market consumers cannot otherwise realistically hope to get. We’ll let the reviewers at Worn and Wound have the last word:

“Overall though, for the price the Mission to Jupiter, and I’d think by extension the other 10 MoonSwatches, are incredibly fun, stylish, and conceptually amazing. It’s hard to quite put it into words, but there is a unique novelty to wearing a plastic Speedmaster. A luxury watch from a famous brand with great historical significance that looks great, and doesn’t cost an arm and a leg. Well, when they are available, that is… They are a new take on the iconic design, an unexpected detour on a historical path that opens up the watch to a whole new market and fanbase. And, the colors are just rad.”

Swatch is used by many pricing and marketing strategy experts as an example of a brand successfully using iconic pricing. Like Costco’s hot dog and soda, which has remained at $1.50 for decades, all Swatch watches cost $40 in the 1980s and 1990s, and the price didn’t change for over a decade. This price is also viewed as instrumental in its successful execution of a breakaway positioning strategy.

The sources for this discussion are Swatch Group’s 2022 Annual Report, its 2023 Half-year Report, and Davis, J. (2022). The inside story of how Omega watches blew up 2022, Esquire.

Note that these are estimates from Morgan Stanley and Hodinkee. Swatch Group does not report unit sales or revenues of its individual divisions or product lines.