Understanding Price Structure [2025]

The price structure is a core concept for effective pricing strategy. A well-designed price structure can increase the organization's realized prices and profit without changing asking prices.

For managers and entrepreneurs, pricing is a complex activity. They can approach pricing decisions with dramatically different mindsets, which will lead to different results. For example, when considering a price increase on a core offering as many companies are doing these days, they could ask, “By how much should we raise our prices?” Or they could frame the issue differently as, “How can we improve our realized prices without raising our asking prices?”

These two questions highlight the distinction between the concepts of the price level and the price structure, which correspond to simplistic and nuanced methods of approaching pricing strategy questions. The price level involves thinking in terms of averages, totals, and percentage changes. The price structure considers assortments of offerings, combinations of prices and benefits, and introduces variations in pricing and offers, among other things, focusing more on the number, range and variation. As we will see in this note, price structure is a far more sophisticated, nuanced, and powerful approach to making pricing decisions and crafting a pricing strategy for an organization.

The Price Level

In everyday conversations, as consumers or managers, we often frame our discussions using price levels. For example, one story noted that the average price of a wedding in the United States declined from $28,000 in 2019 to $19,000 in 2020 because of the COVID pandemic, but had increased to $33,000 by 2024. Another story on the affordability of fast food reported price increases of various fast food offerings over the period from 2014 and 2024, saying:

“From 2014 to 2024, average menu prices have risen between 39% and 100% — all increases that outpace inflation during the given time period (31%). McDonald’s menu prices have doubled (100% increase) since 2014 across popular items — the highest of any chain we analyzed. Popeyes follows McDonald’s with an 86% increase, and Taco Bell is third at +81%. Menu prices at Subway and Starbucks have risen by “just” 39% since 2014 — the lowest among chains we studied. These are also the only restaurants where prices have risen by less than 50%.”

Such reporting and discussions of prices and price changes are common. You will encounter them on a daily basis. These stories are about the price level, which is defined here as “the average price that a company charges for its products.”

The value of the price level lies in quickly providing an overall picture of the company’s prices and pricing performance and in getting an idea of changes. It is a helpful, if somewhat crude, tracking variable. However, the price level has at least three serious limitations.

First, it lacks specificity and hides essential information. Saying that Taco Bell raised its prices by 81% over a decade (or 8% over the previous year) is not particularly informative about the effectiveness of its pricing strategy. This statistic doesn’t provide information about specifics. Also, it does not mean that Taco Bell raised the prices of every single item it sells by exactly 81%. The company may have raised the prices of some items byh more, others by less and could have even lowered the prices of certain items for specific tactical reasons, netting an 81% increase. The price level obscures the details of actual prices and price changes completely.

Second, across-the-board price changes, often deployed in B2B cases (and sometimes in consumer settings), can yield uncertain results. Such increases are readily subject to the penalty of the demand curve. Customers can identify them easily and respond quickly, by negotiating a decrease, going to a competitor, or by buying less. On the flip side, when all prices are lowered equally, customers may not react with enough enthusiasm to make the universal price cuts worthwhile. In many situations, customers have little flexibility in adjusting their responses to a blanket price change in either direction for any number of reasons causing the price action to be unsuccessful.

Third, and perhaps most significantly, relying on the price level alone leads to ineffective, and sometimes downright bad pricing decisions because the repertoire of available pricing options is not considered. The savvy pricing strategist has no leeway to improve price realization. For instance, they cannot take advantage of differences in customer valuations or in customer psychology, or introduce variation in price in any number of ways that make sense. This is why price structure needs to be considerd when making a pricing decision.

The Price Structure

The price structure provides a far more nuanced and useful way to approach pricing decisions. We might even say it is the only good way to think of pricing decisions. The price structure is defined here as “the overall assortment of prices, price-benefit combinations, price variations, and price offers provided by the company to its customers.”

The overall assortment of prices acknowledges that few organizations, even small ones, sell just one product or service1. The pricing strategy must consider the prices of the entire portfolio of offerings such as the company’s product lines, making decisions about how many products and different versions of each product to offer, and then deciding the prices of individual items. These decisions are interrelated due to the substitutability and complementarity of the company’s products. Even more important, it costs relatively little to create different versions of a product and charge different prices for it, adding far more flexibility to the pricing strategy. (see the case of Spotify below).

Price-benefit combinations refer to the correspondence between the features and benefits and the price of each item in the company’s portfolio of offering. In the pricing domain, there are many names for this idea depending on industry such as price pack architecture, product line pricing, product mix pricing, and so on. In all these cases, the core principle is to have some sort of logic behind the prices of all the items being offered such that individual prices make sense as do relative prices. For example, one company may set the prices of different products in one of its lines to maximize their perceived distinction from others in the line, while other may price the items in its line with the goal of maximizing sales of its high-margin products at the expense of the items which it deems to be low margin in its line. Considering price-benefit combinations in pricing strategy requires an understanding of how buyers make purchase decisions and the role played by price in the decision making, not to mention salients aspects of the pricing context.

Price variations acknowledge that prices change frequently in today’s dynamic pricing and low menu costs-driven pricing environment. Just like it is virtually impossible to find true single-product brands, it is very hard to find brands that maintain prices for lengthy time periods. Variable pricing is the de facto standard in pricing strategy. Instead of thinking about one price for any product, it is more useful to think of a range of prices. The pricing strategist must establish the range and decide how much, how often, and when each product’s price should change.

Price offers refer to the specific ways in which prices are temporarily reduced or contextualized to influence customers and encourage purchase behavior. Common methods of doing this include offering discounts of different types, the judicious design of mixed price bundles, using two-part pricing, utilizing the psychological roles of price, and even using narrowly applicable creative niche pricing strategies like extreme-value promotions. There are virtually unlimited ways to design effective price offers, and there are almost as many reasons to do so.

Making pricing decisions by considering the price structure provides the manager or entrepreneur with almost unlimited opportunities to design an effective pricing strategy for their organization.

Simple Versus Complex Price Structures

One way to understand a company’s price structure is by its degree of complexity. Spotify’s price structure in 2018 consisted of two options, Spotify Free, an ad-supported free version, and Spotify Premium at $9.99 per month that was ad-free, and provided shuffle play, offline listening, and higher-quality audio. The Spotify user had a simple binary choice: Use the free service or pay $9.99/month for the premium service. This is an example of a simple price structure. An all-you-can-eat buffet with one standard price, say $15, for everyone all the time is another example.

By 2020, Spotify had changed its price structure as shown in the next figure. It offered an individual plan for $9.99 per month, a duo plan for $12.99, a family plan for up to 6 accounts for $14.99, and a student plan for $4.99. The plans had different trial periods – the first month free for the student plan and two months free for the other plans. The family plan provided additional features like an app for kids, a family mix playlist, and the ability to block explicit music. The student plan bundled ad-supported Hulu and Showtime for cash-strapped students.

Spotify’s price structure in 2020 was relatively more complex than 2018. The next figure shows its most recent price structure, as of the writing of this note in September 2025.

As can be seen in the different iterations, from 2018 to 2020 to 20215, Spotify increased the assortment of prices offering different benefits at different price levels, and bundled specific introductory offers for each plan. It also unbundled the audiobook offering from its music plans in its most recent pricing, charging separately for this service. From a pricing strategy perspective, Spotify’s current price structure (as of 2025) incorporates mixed price bundling, good-better-best pricing, quantity discounts, trial pricing, and customized pricing. The pricing was now explicitly taking advantage of differences in the valuations, willingness-to-pay, and ability-to-pay of different customer segments and differences in the costs to serve them.

How to Improve Realized Prices Without Increasing Asking Prices

A well-designed price structure takes advantage of each of the four pillars of pricing strategy — costs, customer value, reference prices, and the value proposition, in a thoughtful and goal-oriented way. It delivers greater total value to customers by recognizing differences between them while concurrently increasing the company’s revenue and profit, all without necessarily changing the price level2. This is the fundamental benefit of a price structure. The company can improve its realized prices without raising its asking prices.

Let’s consider two examples to illustrate this counter-intuitive but powerful principle: (1) By focusing on higher-margin sales from an existing product assortment, and (2) By shifting from an everyday low price (EDLP) to a hi-lo pricing strategy.

1) By focusing on higher-margin sales from an existing product assortment.

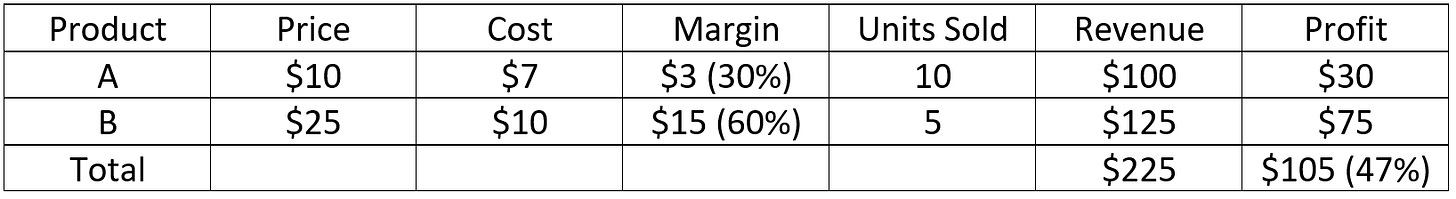

Consider a company that sells economy and premium versions of a product, A and B. A costs $7 to make and is priced at $10. B costs $10 to make and is priced at $25. The margins on A ($3 or 30%) are lower than the margins on B ($15 or 60%).

In the base case, the company’s management hasn’t considered price structure strategically. The company advertises both products equally. The result is that the company sells more units of A (10 units) and fewer units of B (5 units). The company earns a revenue of $225 and a profit of $105 (47%).

The base case

Thinking strategically, the management makes one change: they focus on selling B by shifting all advertising to B (using the same budget as before). This results in fewer sales of A (5 units) and more sales of B (10 units). With this shift, the company earns a revenue of $225 and a profit of $105 (47%).

An emphasis on sales of B

By emphasizing B, the company’s revenues have increased to $275 from $225, and its profit has increased to $165 from $105. The margin also increases, from 47% to 60%. The asking prices have remained unchanged, but because of the company’s focus on selling the higher-margin product, its financial performance has improved from the product’s sales.

Now imagine a third case where customers are more demanding. To achieve the same sales of B as the previous case, the company must not only switch all advertising to B, but also offer a 10% discount to buyers. The customers of B now pay $22.50 instead of $25.

An emphasis on sales of B, with a 10% discount

Comparing this to the base case, we can see that the price level of the company’s products has decreased. But the company still earns higher revenue ($250 vs. $225 in the base case) and higher profit ($140 vs. $105). The customers are paying lower prices, but the company is still making higher revenue and profit. This example illustrates the principle of improving realized prices without raising asking prices or even lowering them.

2) By shifting from EDLP to hi-lo pricing

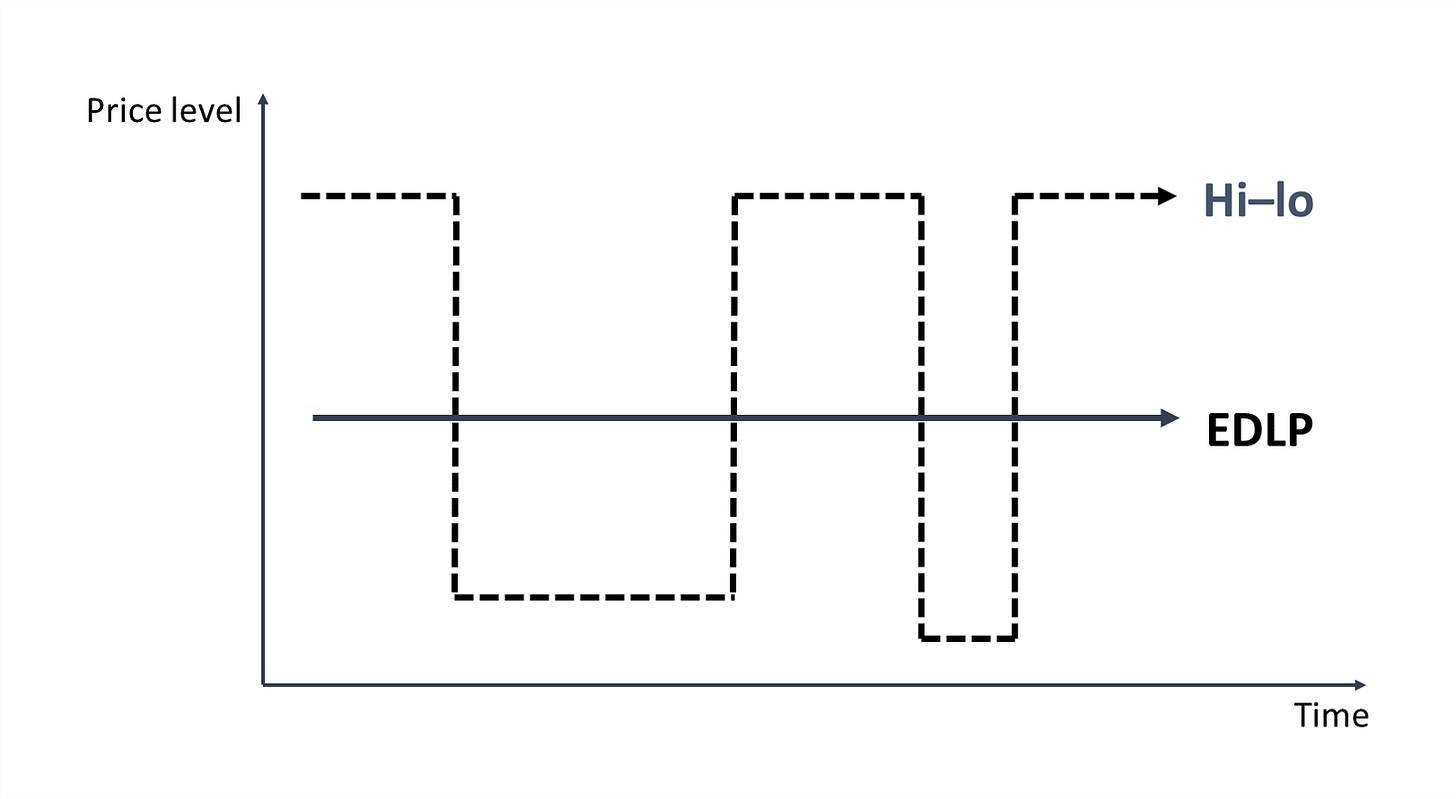

Everyday low pricing is a pricing strategy where the company keeps its prices unchanged over time3. Hi-lo pricing involves selling the product at its regular, higher price some of the time and offering price promotions at other times. Under EDLP, the customer pays the same price no matter when they buy the product. In hi-lo pricing, the price paid depends on the timing of the purchase. EDLP uses a simple price structure, hi-lo pricing uses a more complex price structure. This is shown in the graphic below.

In the base case, consider a company that sells product A using EDLP. It costs $7 to make and is always priced at $10. In this case, the margins on A are $3, and the company is able to sell 10 units of A. The company will earn revenue of $100 and a profit of $30 (30%).

EDLP

The company now shifts from the simpler EDLP price structure to the more complex Hi-lo price structure. They increase the regular (hi) price of A to $15. From time to time, they run promotions, offering A at the low price of $9. The company still sells 10 units of A, 3 units at the hi price to customers who are not price-sensitive, and 7 units at the low price. The company earns revenue of $108 and a profit of $38 (35%) under hi-lo pricing.

Hi-lo pricing

A majority of customers pay a lower price under hi-lo pricing than they did under EDLP. Still, the company earns higher revenue and profit. This is because hi-lo pricing allows the company to capture greater value from the lower price sensitivity and higher willingness to pay of a small minority of customers. A more complex hi-lo price structure allows the seller to discriminate between customers based on their different valuation of A, which is not possible under the simple EDLP price structure.

Tools for Designing a Price Structure

As these two examples illustrate, the price structure provides opportunities to the pricing decision maker to develop more customized price offers. It recognizes differences in what customers want and how much they are willing to pay and makes offers that fit these needs. When designing a price structure, the pricing decision maker can use a variety of different pricing methods and tools. Here is a partial, somewhat broad list that provides a sense of the vast domain of options available to design a price structure:

Give a free trial or introductory discount.

Utilize price promotions, which can take almost limitless forms. The only constraint is creativity (and some good knowledge or predictions about price response).

Offer different prices based on natural or orchestrated fluctuations in demand.

Charge fees for customer affordances (e.g., change fees, resort fees, surge prices).

Vary the price at random intervals.

Use hi–lo pricing instead of EDLP. Hi-lo is a generic term, essentially the levels and timing of prices makes this an infinite option strategy.

Use a good-better-best pricing strategy.

Vary prices for horizontally and vertically differentiated products in the product line.

Use mixed price bundling, but also consider the judicious or limited use of pure bundling.

Avoid all-inclusive prices, partition your pricing as and when possible.

Use loss leaders alone or in combination with other methods.

Use two-part pricing, by requiring a paid membership for access (e.g., Costco)

Discount complementary products.

Design a complex loyalty rewards program.

Use variable pricing or dynamic pricing anchored to demand changes.

Each pricing tool in the list has its own design parameters and considerations for effective use, and each one merits its own in-depth discussion. Plus, as mentioned earlier, this is by no means a comprehensive list of the available tools. New tools are constantly emerging with technology and with a better understanding of buyer psychology. The main lesson is that all the important work for the pricing decision maker lies in choosing and applying these tools and developing an effective price structure for their products.

Conclusion

When the pricing decision maker makes decisions through the lens of the price structure instead of the price level, they have far more flexibility and greater opportunities to improve the performance of their pricing strategy. As a result, they can pursue the seemingly impossible goals of delivering greater value to customers and concurrently increasing the company’s revenue and profit. They can improve price realization, i.e., earn higher prices, without raising asking prices, or even by selectively lowering them. A more complex price structure that accounts for differences between customers will result in bigger payoffs for the company.

I spent quite a bit of time and effort trying to find companies that sell just one product. I homed in on small startups like Chocbox, which became famous on TikTok for its Dubai chocolate making kit, and Veloci, a sneaker startup founded by Rice University undergraduate students that started with a single shoe called Ascent. In both cases, however, the brands have expanded their offerings to sell different types of chocolate (dark, milk) kits and dips in the case of Chocbox and different colors of Ascent and other models in the case of Veloci. It is my contention that brands offering just one item do not exist in equilibrium.

This is the main point, the punch line so to speak, of this note on price structure. The idea that average prices don’t have to be raised at all to increase the net benefit to both customers and the organization seems counter-intuitive at first glance. But this is the fundamental idea behind effective pricing strategy, and indeed, for making price decisions using the lens of price structure.

It is worth mentioning that EDLP in its pure form is more conceptual than practical. Virtually no company fixes it prices over a lengthy period. In the practical sense, an EDLP strategy plays out through narrower price bands, relatively shallow and infrequent price discounts, so that prices appear to change little and infrequently to customers.